- Analysis of white porcelain samples from gangyanzi and guifangzi kiln sites of the western Xia period

Maolin Zhanga, Yimei Jianga, Jianbao Wangb, Yongbin Yuc,* and Haidong Lid

aJingdezhen Ceramic University

bChina Association of Collectors

cArchaeological Research Center of the National Cultural Heritage Administration

dNingxia MuseumThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Scientific analysis of white porcelain unearthed from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites in the Helan Mountains reveals an unusual body composition characterized by high silica and low alumina. The contents of impurity elements such as iron and titanium are particularly low, with iron levels approaching the lowest known values in ancient Chinese ceramic bodies. The glaze composition shows certain similarities to that of the Lingwu kiln, as both belong to the high-temperature calcium glaze system; however, the contents of magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, iron, and titanium are significantly lower than those found in Lingwu white porcelain. The firing temperature of the white porcelain from Guifangzi and Gangyanzi is approximately 1250 °C, and the body is essentially sintered, with evident corrosion of residual quartz and, in some samples, a substantial presence of mullite crystals, indicating a higher firing quality than that of Lingwu kiln products. Due to the exceptionally low levels of iron and titanium impurities, the whiteness of these porcelains is remarkably high, meeting the traditional aesthetic preference for white ceramics in the Western Xia dynasty.

Keywords: Western Xia dynasty, Guifangzi kiln, Gangyanzi kiln, Lingwu kiln, White porcelain.

The Western Xia dynasty, a regime established by a northwestern ethnic minority group, coexisted in confrontation with the Northern Song, Liao, Southern Song, and Jin dynasties from the early 11th to the early 13th century. However, its ceramic industry is scarcely mentioned in historical records. Due to this lack of documentation, The History of Chinese Ceramics, published by the Chinese Ceramic Society in 1982, does not include any reference to Western Xia porcelain. In 1983, the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences discovered a Western Xia kiln site at Ciyaobao in Lingwu, Ningxia. Subsequent excavations at the Ciyaobao, Huiminxiang, and Ta'erwan kiln sites in Wuwei were carried out by the Institute of Archaeology, the Ningxia Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, and the Gansu Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, respectively [1-3]. These efforts revealed the basic characteristics of the Western Xia ceramic industry and helped fill a long-standing gap in the history of Chinese ceramics [4]. However, a comprehensive understanding of its technical achievements requires the application of advanced archaeometric methods. In this context, modern archaeometric investigations have proven pivotal in deciphering ceramic technology. For instance, high-precision elemental profiling is essential for tracing the provenance of specific kiln products [5], while microstructural analysis can elucidate the effects of raw material selection and firing technology on ceramic properties [6]. Notably, such approaches have proven particularly effective in the study of imperial kilns, as evidenced by pigment source analyses in Ming Dynasty blue-and-white porcelains [7]. Guided by this methodological framework, initial scientific analyses have examined the compositional formulas, firing temperatures, and other technical aspects of the Lingwu kiln [8, 9]. This provides a crucial technological baseline for the Western Xia ceramic industry.

In addition to the aforementioned kiln sites, further surveys by researchers have identified two additional Western Xia kiln sites: the Gangyanzi kiln site and the Guifangzi kiln site. The Gangyanzi kiln site is located on the hillside fields around the Gangyanzi Terrace at Chaqikou, Toudaogou, Helan Mountain, approximately 12 km away from Chaqikou itself. The Guifangzi kiln site is situated on the south-eastern side of North Maliangou, the main gully of Helan Mountain, approximately 3.5 kilometres away from the Gangyanzi kiln site. Both sites contain abundant remains of white-glazed and black-glazed porcelain sherds, along with kiln furniture. The fine white porcelain unearthed at these sites exhibits a pure and delicate body and glaze, displaying characteristics of both Jingdezhen Qingbai glaze and Dehua white porcelain. Some scholars have suggested that the Gangyanzi and Guifangzi kiln sites may have served as production bases for daily-use wares supplied to the "Imperial City" of the Helan Mountains [10]. What are the specific characteristics of the white porcelain from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites in terms of composition formula and firing technology? In what ways do they differ from—or relate to—the white porcelain unearthed from the Lingwu kiln? A detailed investigation of these questions will contribute to a clearer understanding of the technical and stylistic features of Western Xia ceramic production and provide an empirical basis for identifying the provenance of imperial-use porcelains excavated from sites such as the Western Xia Imperial Mausoleum and the "Imperial City" in the Helan Mountains.

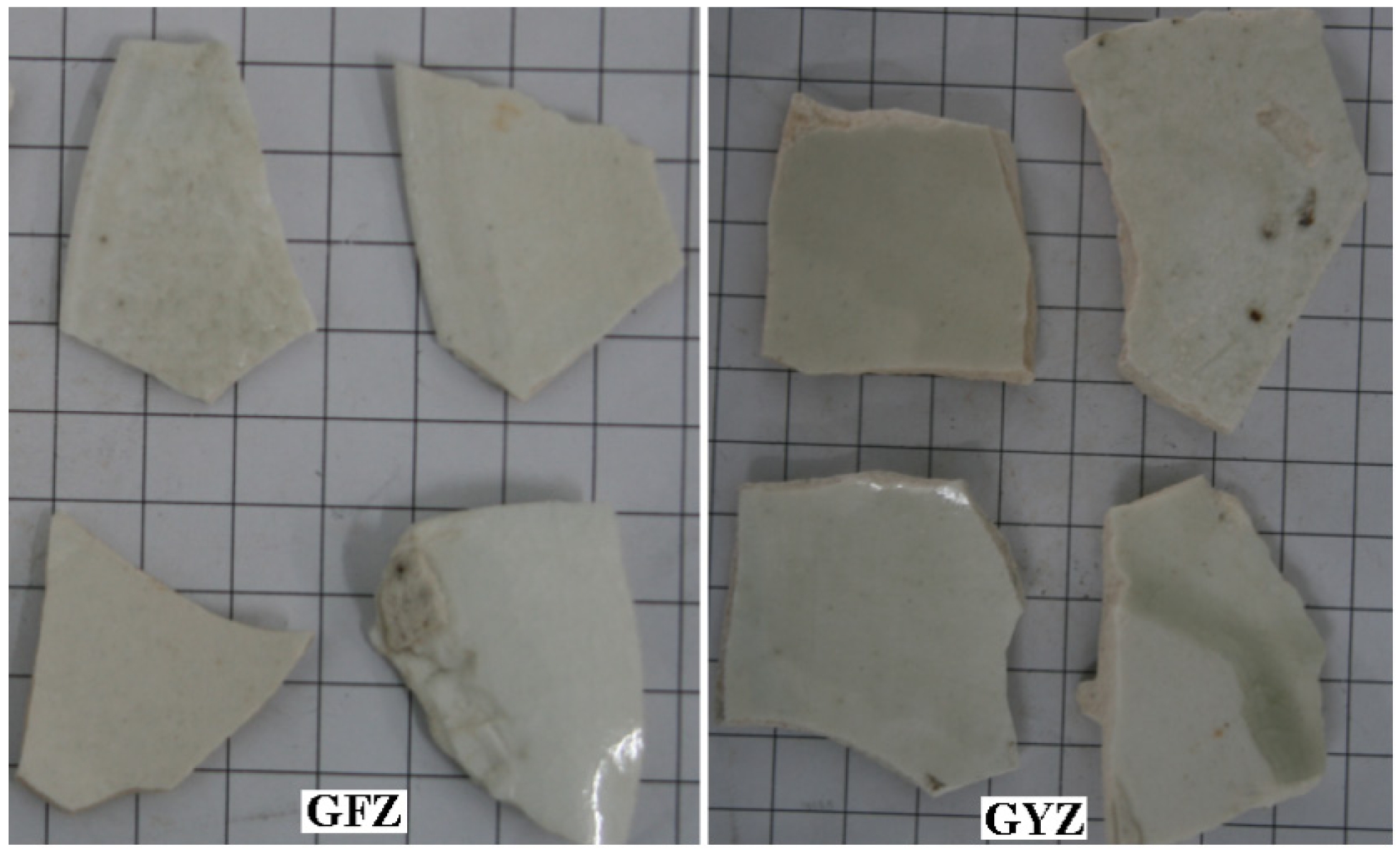

The white porcelain specimens used in this study were collected from the Guifangzi (GFZ) and Gangyanzi (GYZ) kiln sites. Representative sherds are shown in Fig. 1.

The chemical compositions of the porcelain bodies and glazes from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites in the Helan Mountains were analyzed using an Eagle-III energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) spectrometer manufactured by EDAX. In the experiment, a rhodium target and Si(Li) detector were used, with a beam spot diameter of 300 μm, a spectrum acquisition time of 150 s, and quantitative analysis based on a calibration curve method. The results are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Cross-sectional microstructures of the samples were observed using a Prisma tungsten filament scanning electron microscope, equipped with a Thermo Fisher Ultradry EDS detector for surface elemental analysis. Operating conditions included an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, an electron beam (focused beam) diameter of 2–3 μm, a data acquisition time of approximately 60 s, and a dead time of about 60%.

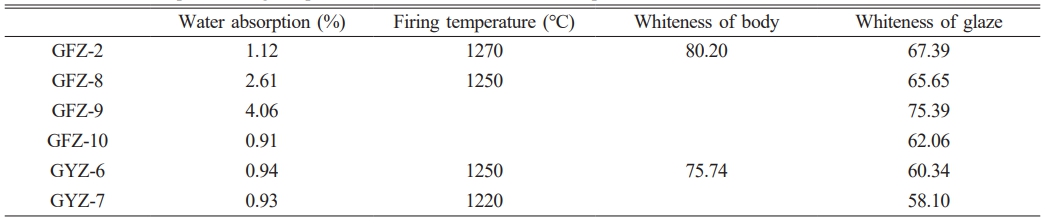

Firing temperatures of selected representative samples were measured using a NETZSCH DIL402C thermal dilatometer from Germany. During testing, dimensional changes occurring before reaching the original firing temperature of the porcelain were interpreted as linear thermal expansion of the ceramic body; changes occurring after exceeding the original firing temperature reflect further transformations due to reheating. Thus, if the body had been underfired, shrinkage would occur upon reheating beyond its original firing temperature, whereas correctly or overfired samples would show expansion. Therefore, the original firing temperature can be inferred from the thermal expansion behavior [8]. Water absorption was determined via the boiling method, and whiteness was measured using an NF333 colorimeter from Denshoku, Japan. The results are summarized in Table 3.

|

Fig. 1 Representative white porcelain samples collected from the Guifangzi (GFZ) and Gangyanzi (GYZ) kiln sites. |

|

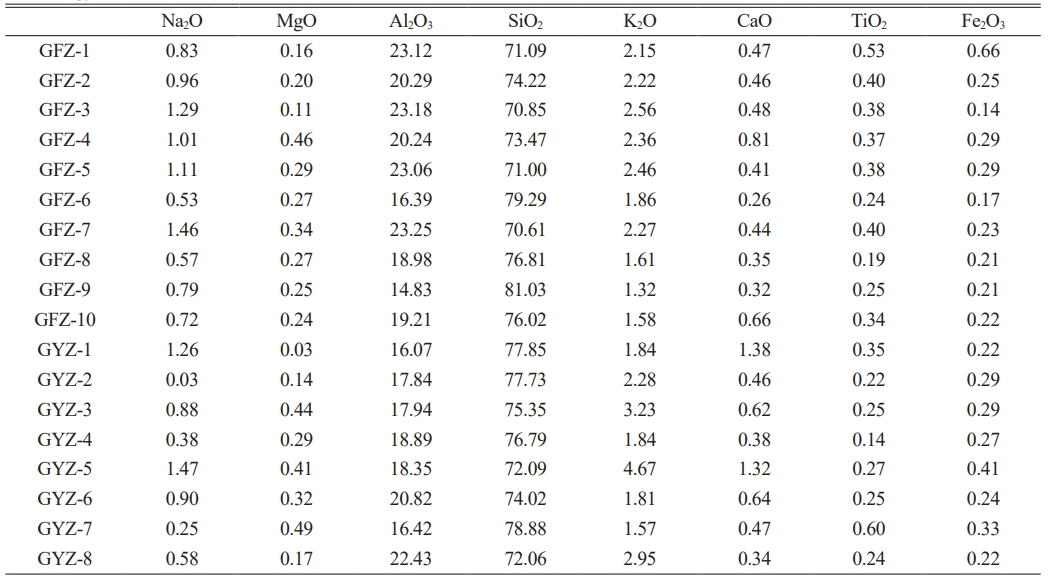

Table 1 Composition of primary and secondary elements (%) in the body of white porcelain samples excavated from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites (%). |

|

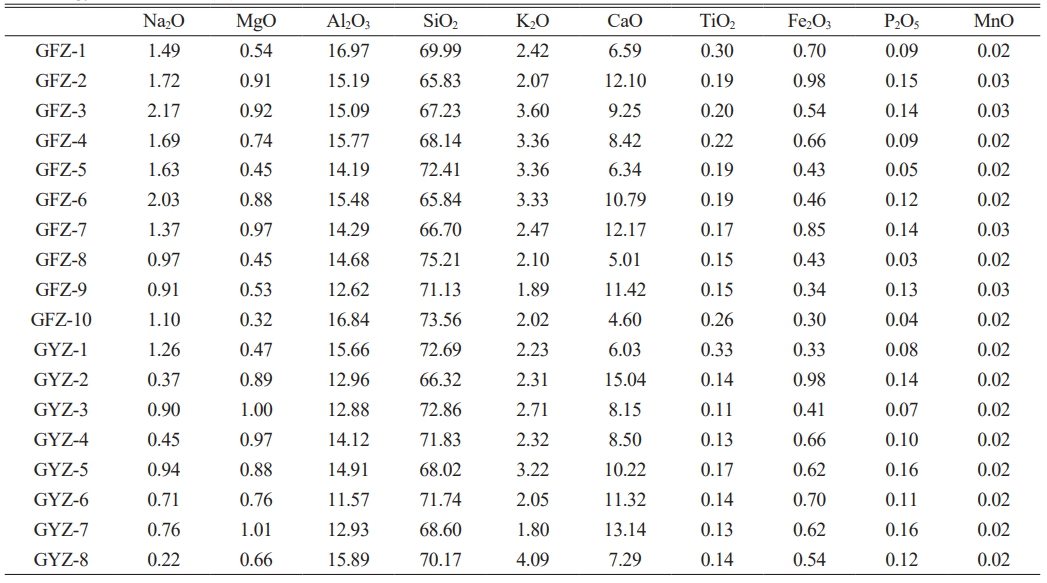

Table 2 Composition of primary and secondary elements (%) in the glaze of white porcelain samples excavated from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites (%). |

Analysis of Porcelain Body Composition

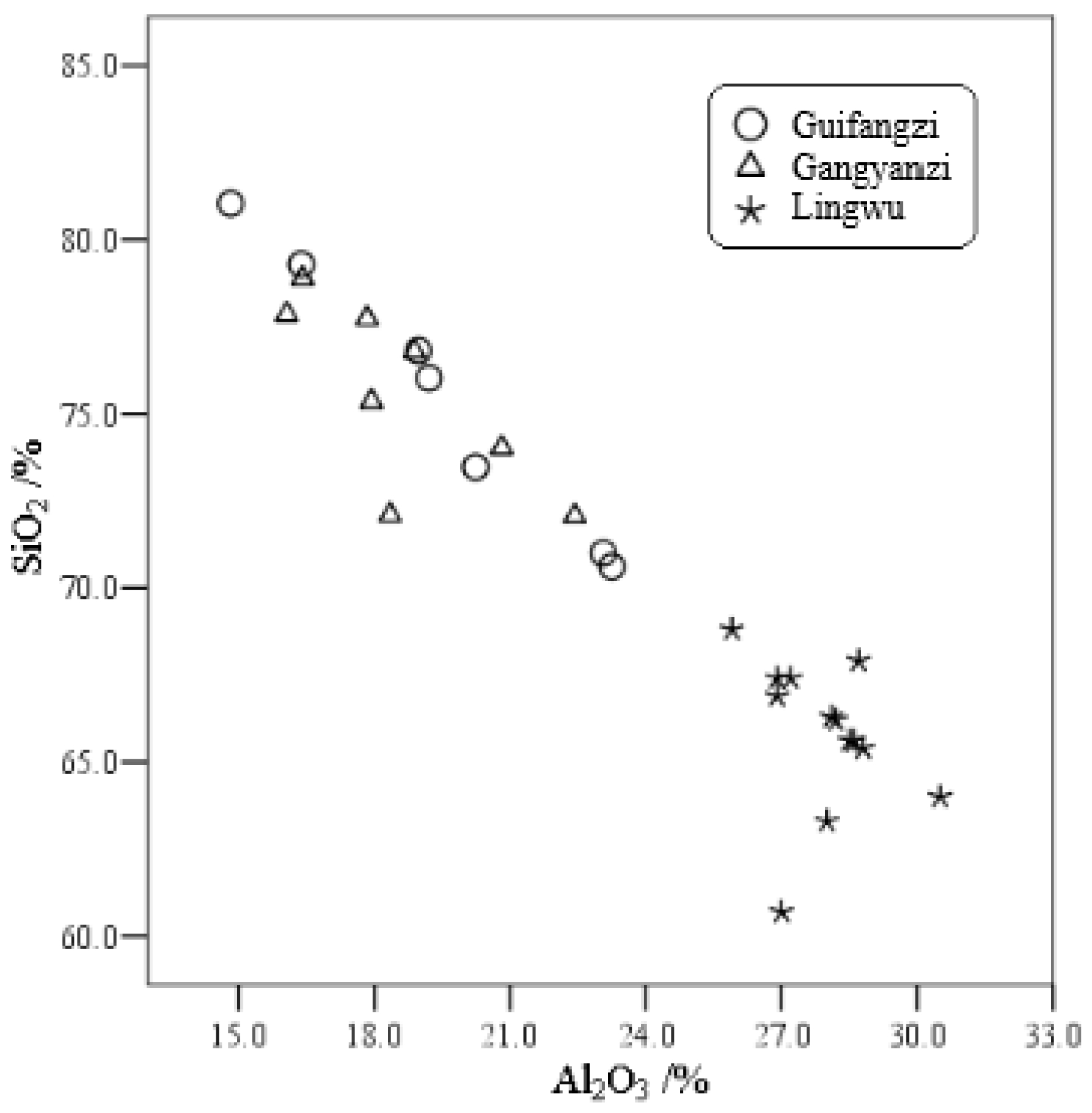

According to the analytical data (Table 1), the content of Al₂O₃ in the white porcelain bodies excavated from the Guifangzi kiln site ranges from approximately 14% to 23%, indicating significant variability, while the SiO₂ content ranges between 70% and 81%. Similarly, the white porcelain bodies from the Gangyanzi kiln site show Al₂O₃ contents between 16% and 22%, and SiO₂ contents between 72% and 79%. This "high-silica, low-alumina" compositional pattern contrasts sharply with that of typical northern Chinese porcelain bodies. For instance, the porcelain bodies produced at the Lingwu kiln—also dating to the Western Xia period—were primarily made from kaolinitic mudstone sourced from coal-bearing outcrops, with average Al₂O₃ and SiO₂ contents of 28.5% and 64.7%, respectively [9]. Clearly, the porcelain bodies from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kilns exhibit a significant compositional departure from the kaolin-rich raw materials commonly used in northern China.

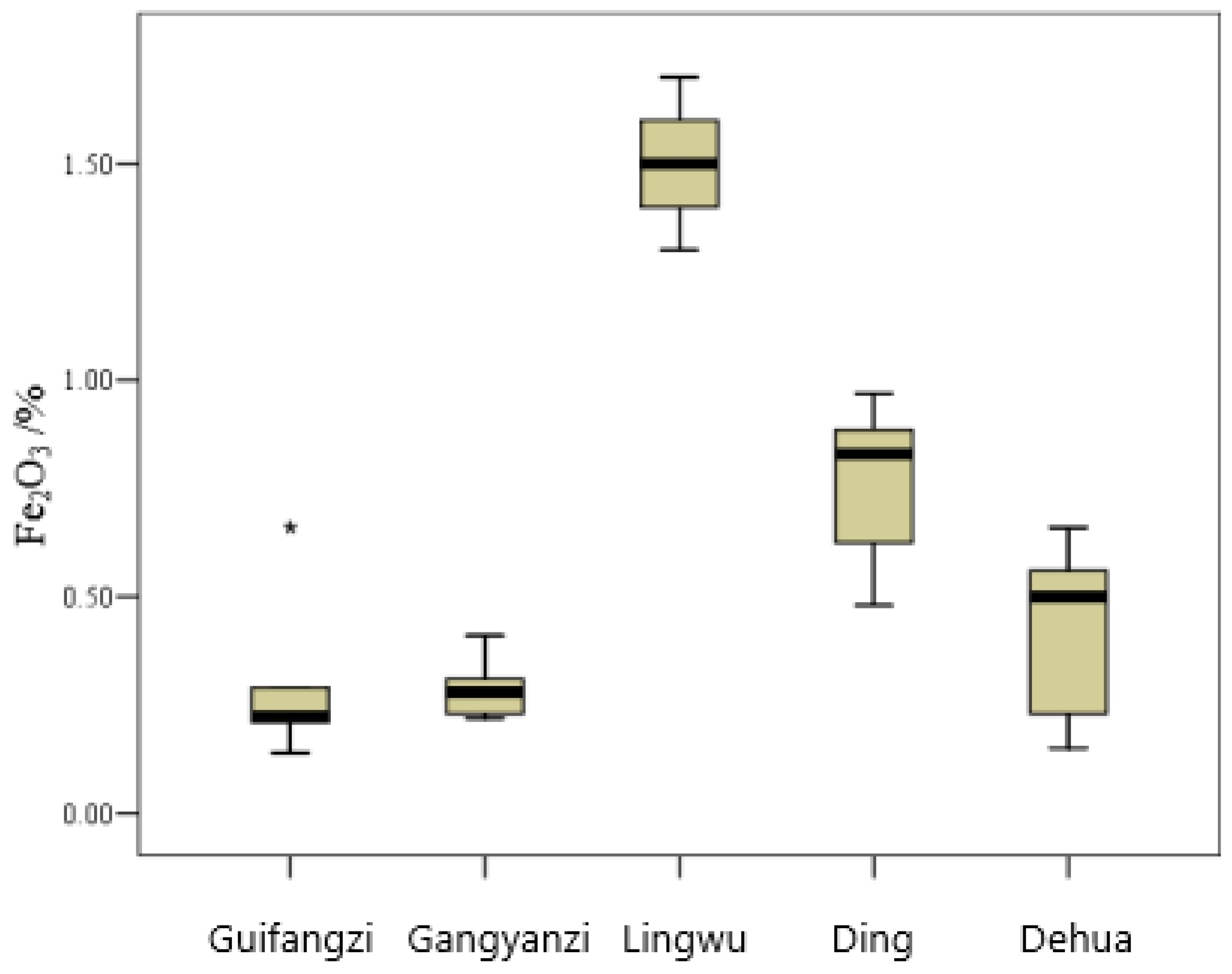

In addition to the levels of silicon and aluminum, the iron content in the porcelain body—an impurity element—is a key distinguishing feature between the products of the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kilns and those of other regions. For example, the white porcelain bodies from the Lingwu Ciyaobao and Huiminxiang kiln sites are often gray, off-white, or beige in appearance, with Fe₂O₃ contents averaging around 1.6%. To enhance their whiteness, a layer of “cosmetic clay” (engobe) was typically applied to the body surface [12]. In contrast, the Fe₂O₃ content in the porcelain bodies from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites is extremely low, with most values falling below 0.3%. This is significantly lower than in white porcelain samples unearthed from the Lingwu kiln, the Ding kiln, and others, and even lower than the Fe₂O₃ content found in Dehua white porcelain from the Ming and Qing dynasties (see Fig. 3. Specifically, the sample sizes were: 10 from Guifangzi (GFZ), 8 from Gangyanzi (GYZ), 13 from Lingwu kiln, 10 from Ding kiln, and 10 from Dehua kiln. Outliers were determined based on interquartile range (IQR) criteria, defined as values beyond Q1 − 1.5×IQR or Q3 + 1.5×IQR). These values represent some of the lowest impurity levels recorded in ancient Chinese ceramic bodies, further underscoring the uniqueness of the raw materials used at the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kilns.

Recent archaeological excavations at the Suyukou kiln site in Helan County, Ningxia, led by the Ningxia Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Fudan University, revealed nearby deposits of ceramic clay, quartz, lime, and coal. The porcelain body recipe was determined to be a binary mixture of ceramic clay and quartz [13]. Dr. Fang Tao of Jingdezhen Ceramic University conducted compositional analysis on these raw materials, finding that the Al₂O₃ content in the ceramic clay reached up to 30.7%, while the Fe₂O₃ content was 1.5%. Whether washing and beneficiation techniques could reduce the Fe₂O₃ content below 0.5% remains to be further investigated.

Overall, this distinct elemental composition provides a reliable scientific foundation for distinguishing the white porcelain of the Lingwu kiln from that of the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kilns, as well as for identifying the provenance of white porcelain unearthed from key Western Xia sites such as the imperial mausoleums.

Analysis of Glaze Composition

As shown in Table 2, the glaze compositions of the white porcelain specimens excavated from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites are largely similar. The SiO₂ content in these glazes is approximately 70%, while Al₂O₃ ranges from 11% to 17%. The contents of CaO and K₂O, which act as primary flux agents, show considerable variation: CaO ranges from a minimum of 4.6% to over 15%, and K₂O fluctuates between 1.8% and 4.1%. With regard to impurity elements affecting color tone, the Fe₂O₃ content is consistently below 1%, averaging 0.57%, and TiO₂ is around 0.2%. Overall, these glazes can be categorized as part of the calcium glaze system. The contents of P₂O₅ and MnO in the glazes from Guifangzi and Gangyanzi are relatively low—approximately 0.1% and 0.03%, respectively—which suggests the addition of plant ash in the glaze formulation. According to related studies, pine ash typically contains roughly equal amounts of P₂O₅ and MnO, while Langjicao (Osmunda japonica), commonly used in Jingdezhen glaze recipes, yields a higher MnO than P₂O₅ content. In contrast, ashes derived from rice straw, sorghum stalks, and poplar wood contain more P₂O₅ than MnO [14, 15]. Given the environmental conditions near the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites, it is likely that poplar ash was used in the glaze composition, though this hypothesis requires further sampling and analytical verification.

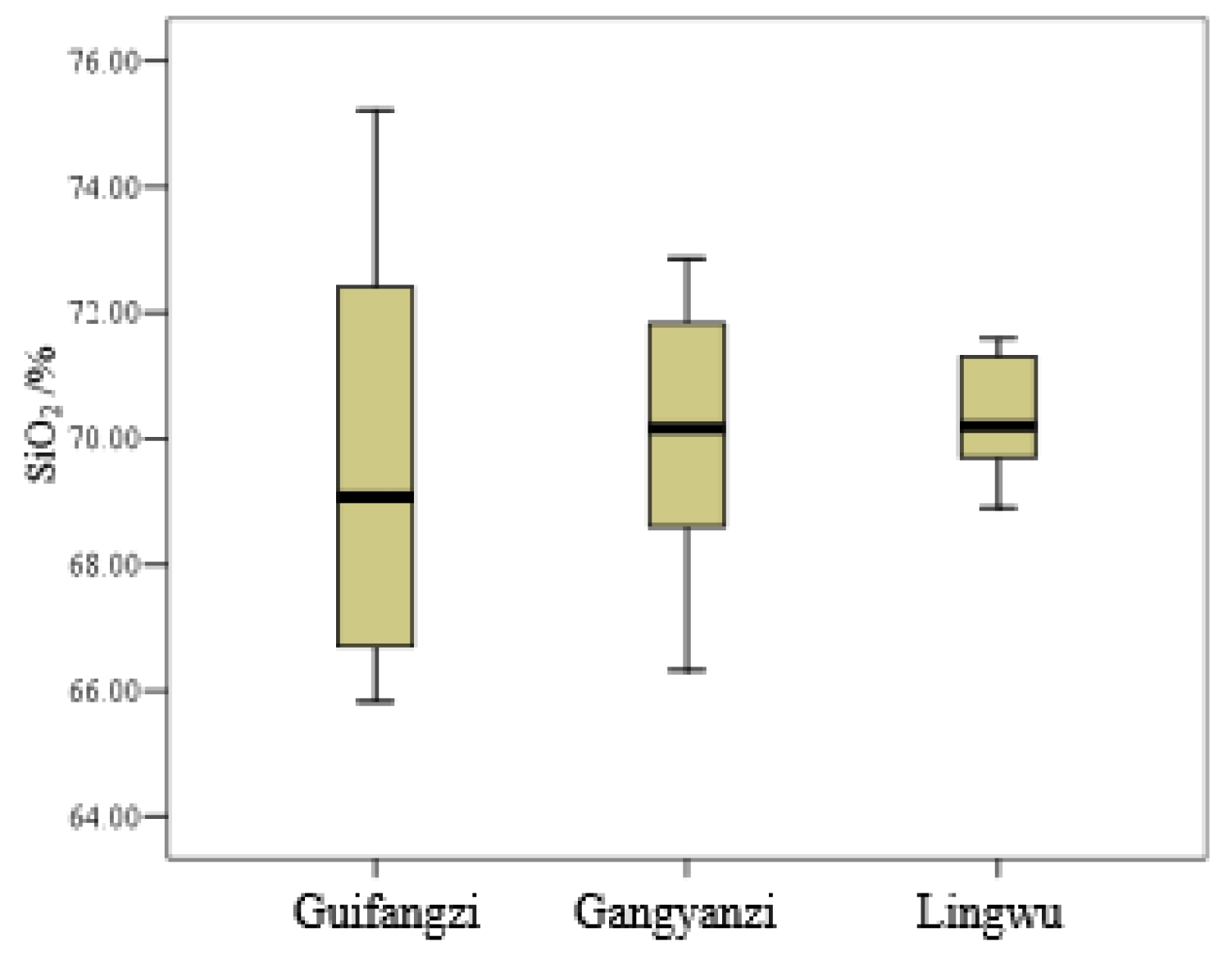

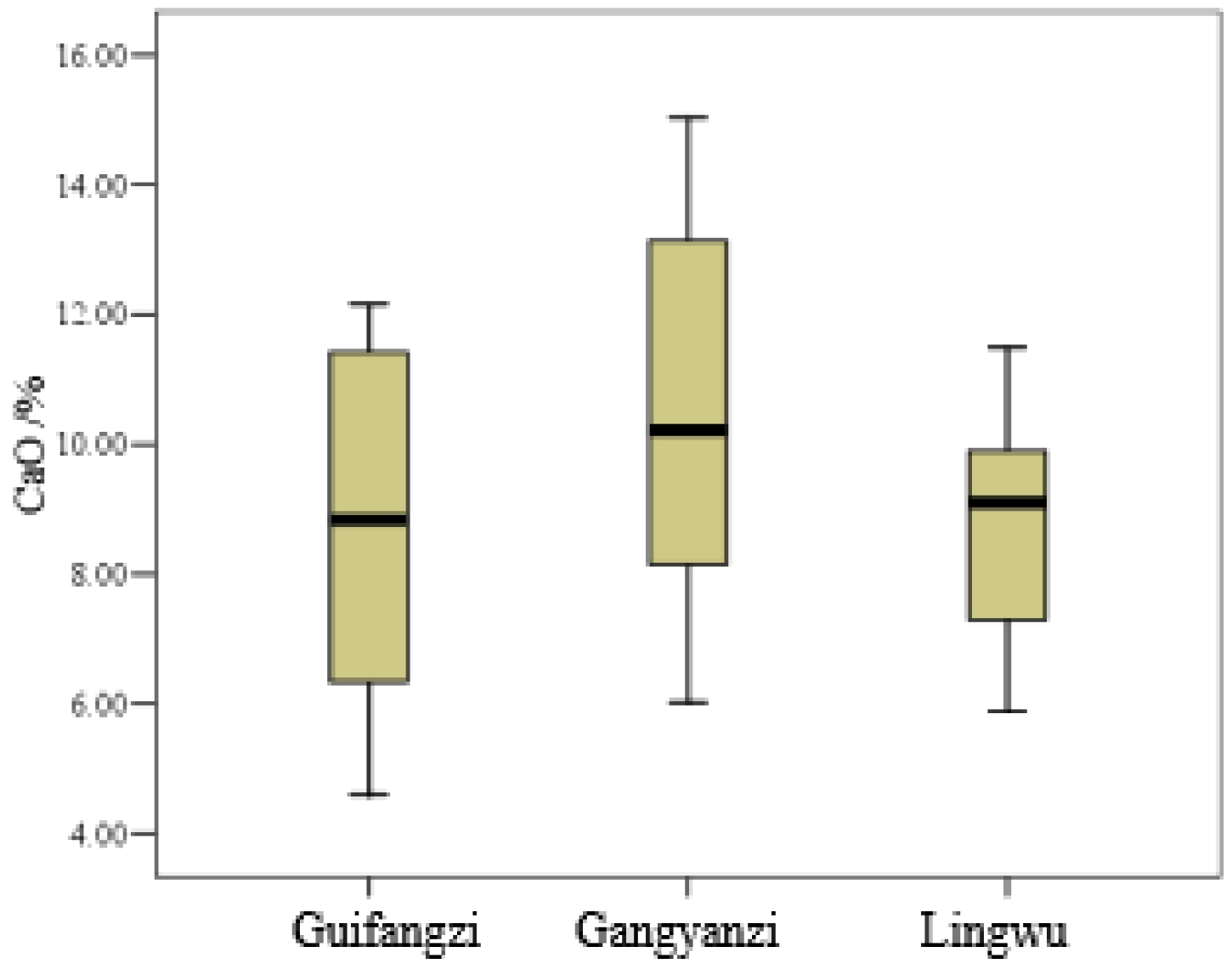

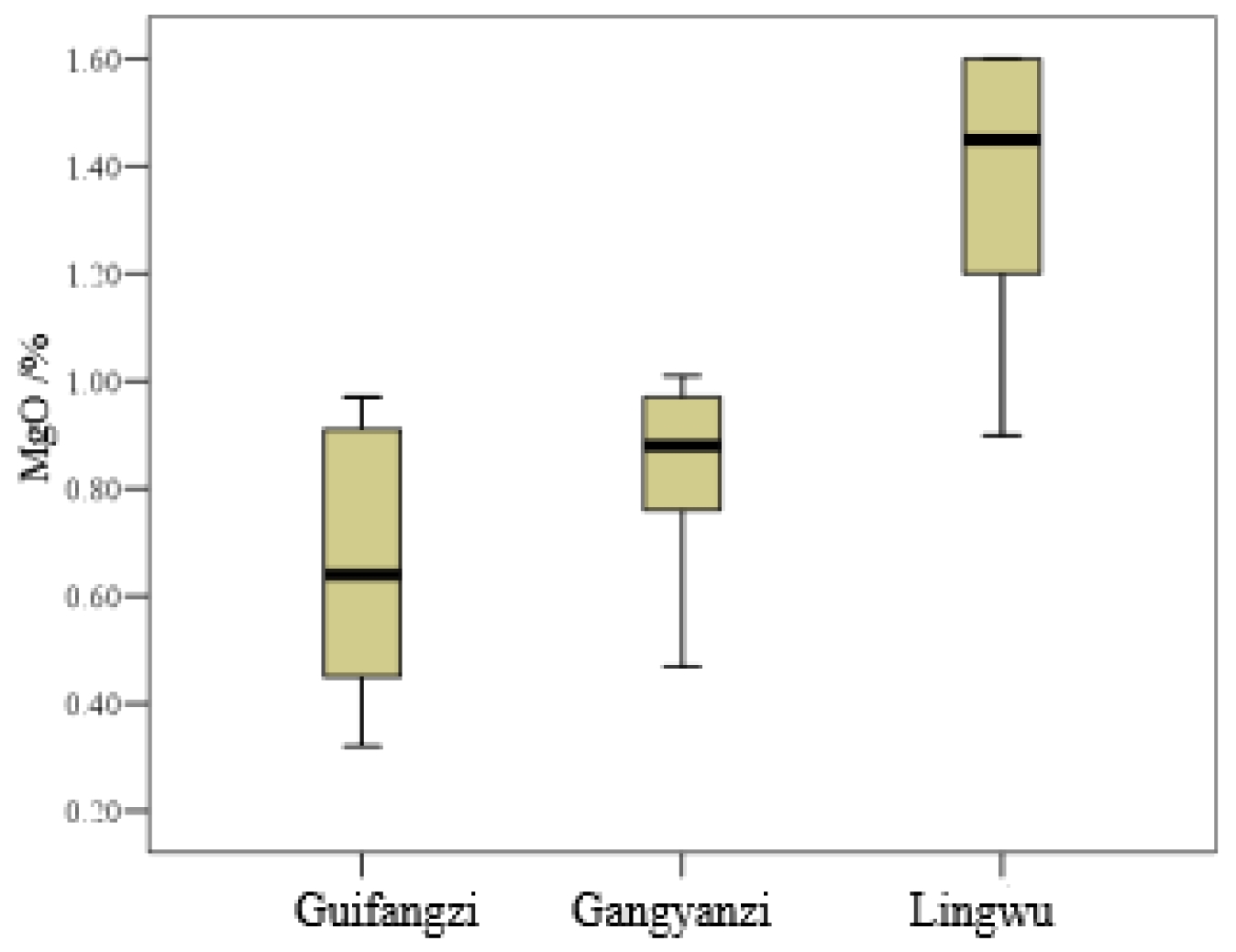

According to the results of this study and comparative analyses conducted by other scholars on white porcelain unearthed from the Lingwu kiln, the glaze compositions of the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi samples are generally similar to those of Lingwu white wares. For instance, the contents of SiO₂, Al₂O₃, and CaO fall within comparable ranges (see Figs. 4 and 5). However, some subtle differences in glaze composition can still be observed. The MgO content in the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi glazes is consistently below 1%, whereas the corresponding value in Lingwu glazes typically exceeds 1%, averaging around 1.3% (see Fig. 6). In the context of traditional Chinese high-temperature glazes, CaO typically serves as the primary flux, while MgO usually occurs as an associated component. There is no evidence of the intentional addition of Mg-rich materials in ancient glaze formulations. Therefore, the observed differences in MgO content between the Helan Mountain white wares and those from the Lingwu kiln are more likely attributable to inherent variations in raw materials, such as the specific type of limestone used in glaze preparation.

Additionally, the MnO, P₂O₅, Fe₂O₃, and TiO₂ contents in the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi glazes are notably lower than those in the Lingwu kiln glazes. This can be attributed to two main factors: the use of clay with fewer impurities in the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi glaze recipes, and a reduced proportion of plant ash. Given that plant ash typically contains relatively high levels of Fe and Ti impurities, reducing its usage would evidently contribute to enhancing the whiteness of the porcelain glaze.

Analysis of Physical Properties

As shown in Table 3, the firing temperature of the white porcelain unearthed from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites is approximately 1250 °C, and the average water absorption rate is around 1.7%. These results indicate that the porcelain bodies from both sites achieved a near-complete sintering state. According to the relevant literature, the typical firing temperature for Lingwu kiln white porcelain ranges from 1100 °C to 1150 °C, with only a few samples reaching up to 1200 °C. Clearly, the firing quality of the white porcelain from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kilns was superior to that of the Lingwu kiln products, reflecting a deliberate effort to meet the exacting standards of the Western Xia royal court. The porcelain bodies from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi sites also exhibit high whiteness values, generally exceeding 75. This is primarily attributed to the extremely low Fe₂O₃ content in the porcelain bodies. This conclusion is consistent with other studies on northern Chinese ceramics. For example, Sang et al. (2022) demonstrated that in Yaozhou celadon, the total Fe₂O₃ content is directly proportional to glaze color depth [16].

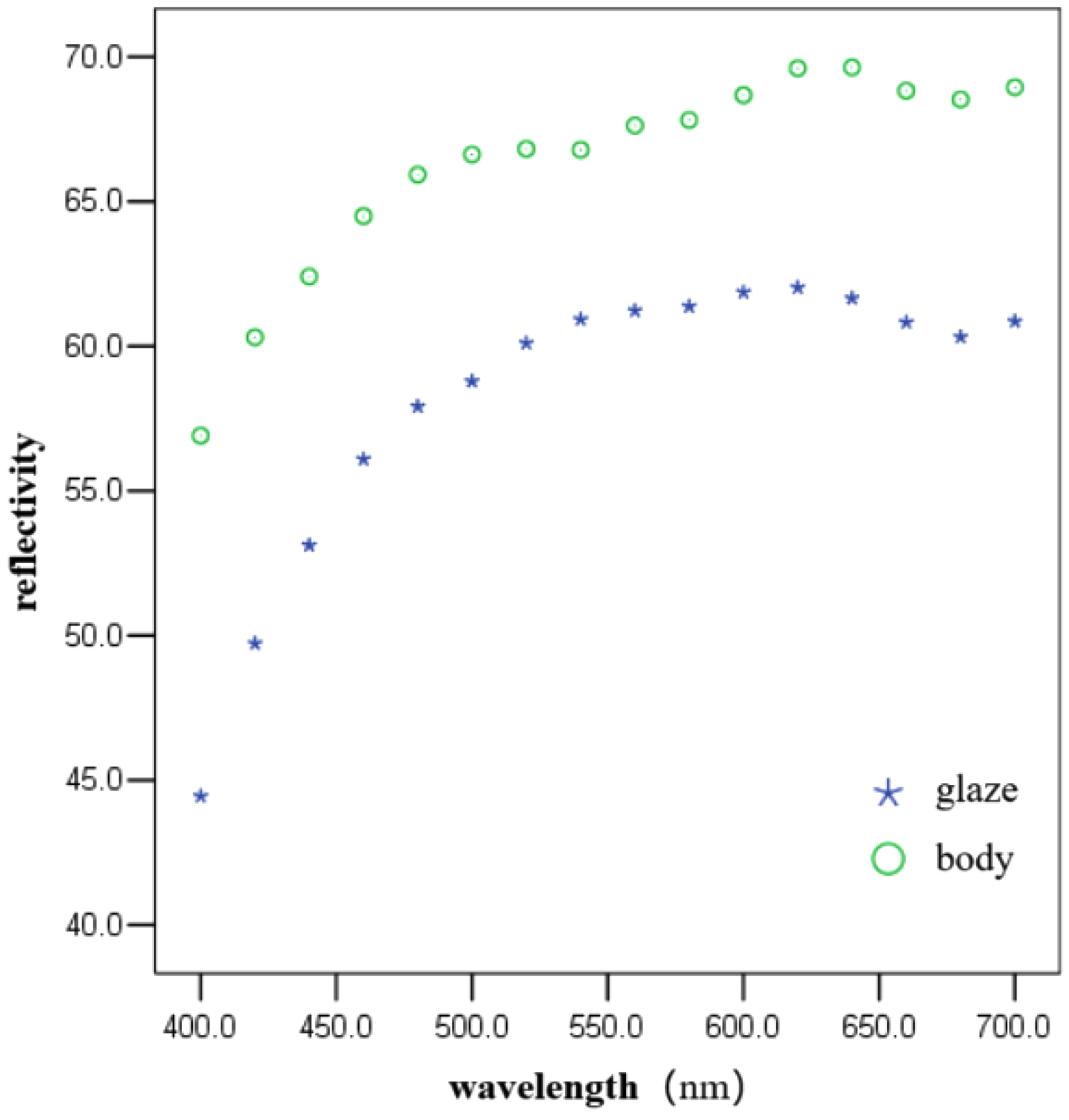

The whiteness of the glaze surface is slightly lower, averaging around 64, which is comparable to that of white porcelain produced at the Ding and Dehua kilns [17]. As shown in Figure 7, the reflectance spectrum of sample GFZ-2 indicates that the porcelain body reflects more than 65% of visible light, while the glaze reflects slightly less, typically between 55% and 60%. This slight difference in whiteness can be attributed to the use of transparent glazes on the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi wares. In general, as the thickness of the glaze layer increases, light transmittance and absorption are enhanced, while reflectance and scattering are reduced, thereby lowering the apparent whiteness of the glaze surface.

Microstructural Analysis

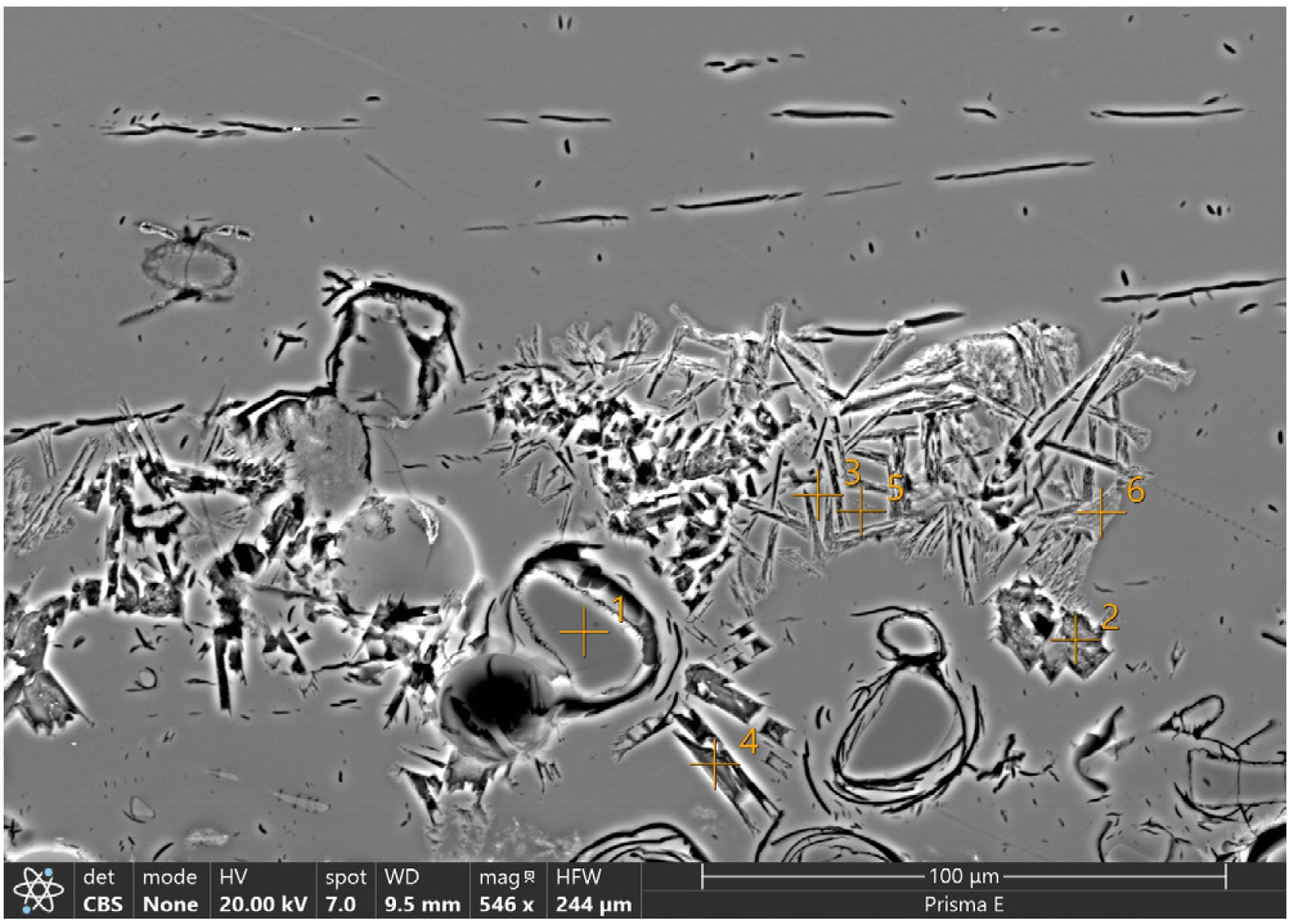

Figs. 8 and 9 present the microstructures of the glaze-body interface of sample GFZ-2 and the porcelain body of sample GYZ-8, respectively. The glaze layer of the analyzed white porcelain appears relatively pure, with few residual crystals and minimal porosity. At the glaze-body interface, needle-shaped crystals are observed (e.g., in positions 3, 5, and 6 in Fig. 8). Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) indicates that these needle-shaped crystals are mainly composed of Si, Al, O, and Ca, suggesting they are likely anorthite.

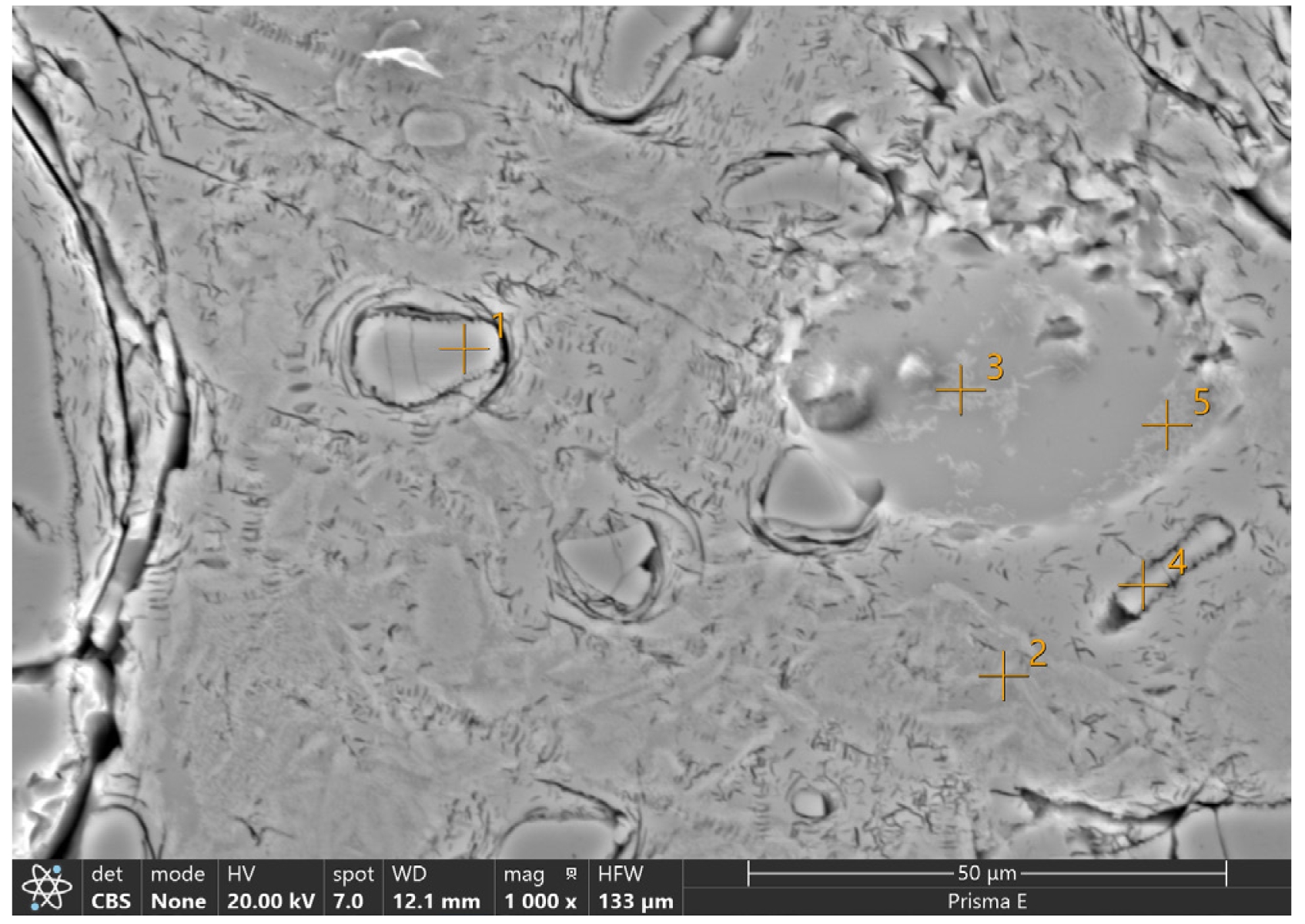

As seen in Figs. 8 and 9, the porcelain bodies from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites contain abundant glassy phases and a large number of residual quartz particles, which is consistent with the high SiO₂ content revealed by EDXRF analysis. These residual quartz particles exhibit signs of thermal corrosion, appearing rounded and dull in shape. In addition, numerous needle-like crystals are observed in Fig. 9, with EDS indicating a composition of Si, Al, and O—characteristic of mullite crystals [18]. The features of the porcelain body microstructure also corroborate the firing temperature of approximately 1250 °C as determined by thermal expansion analysis.

|

Fig. 2 Scattergram of SiO2 and Al2O3 content in white porcelain bodies from Guifangzi, Gangyanzi and Lingwu kilns. |

|

Fig. 3 Box plot of Fe2O3 content in the white porcelain bodies from Guifangzi and Gangyanzi. |

|

Fig. 4 Box plot of SiO2 content in white porcelain glaze of Guifangzi, Gangyanzi, and Lingwu kilns. |

|

Fig. 5 Box plot of CaO content in white porcelain glaze of Guifangzi, Gangyanzi, and Lingwu kilns. |

|

Fig. 6 Box plot of MgO content in white porcelain glaze of Guifangzi, Gangyanzi, and Lingwu kilns. |

|

Fig. 7 The reflectance spectrum of sample GFZ-2. |

|

Fig. 8 Microstructure of the glaze-body interface in sample GFZ-2. |

|

Fig. 9 Microstructure of the porcelain body in sample GYZ-6. |

The white porcelain unearthed from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites of the Western Xia period exhibits an anomalous body composition characterized by high silica and low alumina, coupled with exceptionally low levels of impurity elements such as iron and titanium. In particular, the iron content approaches the lowest values recorded among ancient Chinese ceramic bodies. The glaze compositions of these porcelains show certain similarities to those of the Lingwu kiln, as both belong to the high-temperature calcium glaze system; however, the contents of magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, iron, and titanium are significantly lower in the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi samples than in those from Lingwu. These marked compositional differences provide a reliable scientific basis for distinguishing between the white porcelain of the Lingwu kiln and that of the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kilns, and for determining the provenance of royal-use porcelains excavated from sites, such as the Western Xia Imperial Mausoleum.

The firing temperature of the white porcelain from the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi kiln sites is approximately 1250 °C, with the bodies achieving a near-complete sintering state, as evidenced by the clear vitrification of residual quartz and the presence of mullite crystals in some samples, indicating a higher firing quality compared to the white porcelain of the Lingwu kiln. Due to the extremely low iron and titanium impurity levels, the whiteness of the Guifangzi and Gangyanzi porcelains is remarkably high, fulfilling the traditional aesthetic preference for white ceramics during the Western Xia dynasty.

We sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their valuable comments and thoughtful suggestions, which have greatly contributed to the refinement and improvement of this article. This research was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Project No. 22VJXG025) and the Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Ningxia (Project No. 24NXBZS01). We also wish to express our appreciation to the local scholars and heritage professionals who generously shared their expertise and insights during the course of this study and the Project of Jiangxi Provincial Social Science Foundation (Project No. 25TQ09D).

- 1. Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in “Ningxia Lingwu Kiln Excavation Report” (Encyclopedia of China Press, 1995) p. 6.

- 2. H. Wang, G. Zhou, and Y. Pang, Archaeol. Cult. Relics. [3] (2004) 8-11.

- 3. C. Sun, Y. Du, J. Yu, and R. Yang, Archaeol. [8] (2002) 59-68.

- 4. S. Peng, Inner Mong. Cult. Relics Archaeol. [1] (2009) 110-117.

- 5. M.S. Tite, Archaeometry. 50[2] (2008) 216-231.

-

- 6. I. Erdogan, H. Kursun, U. Onen, T. Boyraz, and T. Kursun, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 26[5] (2025) 703-716.

-

- 7. X. Li, W. Dong, Q. Bao, Z. Chen, Y. Yang, K. Liu, and J. Zhou, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 26[5] (2025) 742-753.

-

- 8. G. Li, W. Ma, and L. Gao, Chin Ceram. [1] (1991) 51-57.

- 9. Y. Song, X. Wang, X. Li, and Q. Ma, Chin Ceram. 46[11] (2010) 71-77.

- 10. Y. Zhang and J. Wang, J. Natl. Mus. Chin. [9] (2011) 92-97.

- 11. M.S. Tite, Archaeometry. 11[1] (1969) 131-143.

-

- 12. C. Lyu, J. Palace Mus. 4 (2006) 86-97.

- 13. C. Zhu, P. Chai, J. Zheng, M. Li, and X. Ren, Archaeol. [7] (2023) 79-98.

- 14. Z. Ye, in “Introduction to the Science of Ancient Chinese Ceramics” (China Light Industry Press, 1982) p. 20.

- 15. M.K. Misra, K.W. Ragland, and A.J. Baker, Biomass Bioenergy. 4[2] (1993) 103-116.

-

- 16. Z. Sang, F. Wang, X. Yuan, S. Shen, J. Wang, and X. Wei, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 23[6] (2022) 758-765.

-

- 17. J. Wu, T. Hou, M. Zhang, Q. Li, J. Wu, J. Li, and Z. Deng, Stud. Conserv. 59[5] (2014) 341-349.

-

- 18. N.T.T. Thao and B.H. Bac, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 24[3] (2023) 471-47.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 933-939

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.933

- Received on Jun 18, 2025

- Revised on Jul 29, 2025

- Accepted on Aug 29, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

introduction and research aims

samples and methods

discussion and analysis

conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Yongbin Yu

-

Archaeological Research Center of the National Cultural Heritage Administration

Tel : (+86) 15179867793 - E-mail: 398155862@qq.com

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.