- Influence of waist reduction structure on internal flow field and heat field of gourd-shaped kiln

Changta Lia, Caishui Jiangb and Junming Wub,*

aJingdezhen University, Jingdezhen 333000, China

bSchool of Archaeology and Museology, Jingdezhen Ceramic University, Jingdezhen 333403, ChinaThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

By reviewing the structural dimensions of the gourd-shaped kiln and conducting on-site measurements of reconstructed and refired kilns, the basic structural data of the gourd-shaped kiln were obtained. Subsequently, a structural calculation model of the gourd-shaped kiln was constructed using 3D modeling software. Computational fluid dynamics software, FLUENT 16.0, was then used to conduct a numerical simulation study of the temperature field and flow field inside the kiln. The results show that during the firing process, the gourd-shaped kiln can reach a maximum firing temperature of 1330 °C.Notably, in the constricted waist area of the kiln, the temperature variation between the front and rear is most significant, with a maximum difference of 40 °C. Moreover, the flue gas velocity at the top of the kiln can reach a maximum of 2.3 m/s, forming a reverse flame flow pattern. After passing through the constricted waist area, the flue gas velocity decreases from a maximum of 1.5 m/s to 0.5 m/s. Finally, through fitting analysis of the numerical simulation data and on-site measurement data, the correctness of the numerical simulation parameter settings in this model was verified, providing a reliable basis for the parameter settings of numerical models in subsequent studies on the structural evolution of the gourd-shaped kiln.

Keywords: Gourd-shaped kiln, thermal engineering theory, Temperature field, Flow analysis.

The gourd-shaped kiln is a unique porcelain kiln specific to Jingdezhen. It combines the advantages of the dragon kiln from the Song and Yuan dynasties and the mantou kiln, featuring distinct structural characteristics suitable for small-scale production [1]. The gourd-shaped kiln made outstanding contributions to the development of Jingdezhen’s porcelain industry and the formation of Qing dynasty town kilns. Therefore, employing modern computer technology to study the structure of the gourd-shaped kiln and providing a theoretical basis for its structural evolution will significantly advance the research on ancient kilns.

The structure of the gourd-shaped kiln is simple, but the complex internal flow affects the firing process and the product pass rate. In previous studies on the flow field and temperature field inside the gourd-shaped kiln, limitations in experimental conditions and research methods resulted in a relatively superficial understanding of the impact of the gas flow field and temperature field within the kiln.

In recent years, with the rapid development of computer science and technology, many researchers have employed computer-based numerical simulation methods to study kiln firing performance [2-4], achieving significant research results [5, 6]. For instance, Li et al. [7] adopted the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software FLUENT to conduct numerical simulations on the flame space of an oxy-fuel fired glass furnace. Specifically, they incorporated the standard k-ε turbulence model, eddy dissipation concept (EDC) reaction model, and discrete ordinates (DO) radiation model into the simulation framework. Yan et al. [8] addressed the issue of high energy consumption in down-draft kilns by proposing the introduction of high-temperature air combustion (HTAC) technology. Furthermore, they utilized the CFD software FLUENT to simulate the temperature field and species field of the novel down-draft kiln configuration. By varying the fuel injection velocity, the distributions of temperature and species fields inside the kiln were systematically analyzed. Zeng et al. [9] developed a substructure coupling simulation method for a ceramic wide-body tunnel kiln and used commercial fluid software to construct a model and perform numerical calculations for the overall combustion system of the tunnel kiln. Pan et al. [10] used FLUENT software to numerically simulate the gas flow field and temperature field of the regenerative structure in the preheating zone of a wide-body roller kiln, determining the influence of the regenerative structure on the temperature field distribution in the preheating zone. Wang et al. [11] analyzed the variations in heat, gas temperature, material temperature, and kiln wall temperature along the length of a rotary kiln during the reduction roasting process of limonite, finding that the calculated results were consistent with the measured results. Lu et al. [12] conducted a study on a 9 m diameter varying rotary kiln for pellet experiments at Jiuquan Iron & Steel Company using CFD numerical simulation technology. Jin et al. [13] constructed a geometric model in accordance with the corresponding dimensions and established a three-dimensional mathematical model for the combustion space of a unit glass furnace. On this basis, they conducted numerical simulation studies on the FLUENT platform, investigating the distributions of temperature field, velocity field, and pressure field as well as the gas flow characteristics within the flame space. Geng et al. [14] employed commercial computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software to carry out numerical simulation investigations on the temperature field and velocity field of molten glass within a continuous cross-fired glass furnace under operational conditions. Yang et al. [15] combined thermal balance analysis with the variation law of gas thermodynamic properties and used FLUENT to simulate the internal temperature field and velocity field of the regenerator under different parameters, analyzing the influence of each parameter on the thermal efficiency of the regenerator. Wang et al. [16] proposed energy-saving, lightweight, long-life, and high-efficiency refractory material configurations for a titanium dioxide rotary kiln, addressing issues with refractory materials by introducing low-thermal-conductivity composite bricks, high-strength acid-resistant bricks, spalling-resistant refractory clay bricks, and mullite-andalusite bricks. Wen et al. [17] utilized the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software FLUENT to simulate the flow field and temperature field inside a brick-and-tile kiln. From the perspectives of fluid mechanics and thermodynamics, they analyzed the flue gas flow characteristics within the brick-and-tile kilns dating back to the Han Dynasty.

Zhang et al. [18] established physical and mathematical models for the heat transfer process of heat pipe heat exchangers, and further performed numerical solutions to these models. Delpech et al. [19] studied radiant heat pipe ceilings in order to improve heat recovery in the cooling phase. Taking the cement rotary kiln as the center of discussion, Akram et al. [20] examined the thermodynamics of rotary kilns, energy losses, the selection of refractory materials and their effects, temperature profiles of rotary kilns, and various examples of loss recovery from excessive kiln shell temperatures. Brough et al. [21] conducted an experimental study of a mild steel heat exchanger model designed for extracting waste heat from a kiln in order to make comparisons and to establish that the phase-change material improved the waste heat recovery rate. S. Muna et al. [22] successfully expanded a two-dimensional filtration combustion model in FLUENT using user-defined functions (UDFs) into a three-dimensional model to study the behavior of real systems. Yi et al. [23] conducted a detailed two-dimensional numerical investigation of the highly exothermic nature of refractory material synthesis, employing a two-dimensional pseudohomogeneous model. Ahmada et al. [24] examined the chemistry and phase constitution of raw materials used in local brick kilns, performing phase and microstructural analyses of fired bricks from local kilns and comparing them with laboratory-made bricks.

However, most researchers have focused their studies on modern kilns such as roller kilns and tunnel kilns [25-30], with relatively few studies examining the scientific and rational aspects of ancient kilns [31]. This paper establishes a three-dimensional solid model and uses numerical simulation methods, combined with theoretical knowledge of heat transfer and fluid mechanics, to analyze the impact of the gourd-shaped kiln’s unique constricted waist structure on its firing performance. The significance of this work lies in its thermodynamic analysis of a traditional kiln. This analysis helps the field understand the reasons for structural changes in kilns throughout their historical evolution. Additionally, it provides insights for optimizing future kiln designs. Additionally, it explores in detail the effects of the gourd-shaped kiln’s distinctive structure on the distribution of the gas flow field and temperature field within the kiln.

Numerical Model

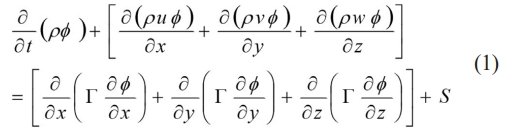

This study is based on the blueprints of the reconstructed and refired gourd-shaped kiln in Jingdezhen, combined with actual on-site measurement data. Using the 3D drawing software AutoCAD, a physical model of the gourd-shaped kiln was created. The kiln’s internal length is approximately 7.5 m, divided into two chambers: the front chamber, which is about 2.8 m long, and the rear chamber, which is about 4.7 m long. The front chamber is taller and wider, while the rear chamber is shorter and narrower. The front end of the kiln has a kiln door, a firebox, and an ash pit. The kiln door is approximately 2.3 m high and 0.6 m wide. Inside the kiln door is a rectangular firebox measuring about 1.2 m wide and 0.7 m long, with the ash pit located about 1 m below the kiln floor. The rear of the gourd-shaped kiln has a square chimney approximately 8 m high. Each side of the kiln top has six fuel replenishment holes, and there are three observation holes located centrally at the front and rear of the kiln top. The entire kiln bed slopes upward from front to back with a gradient of 5 degrees. As a vessel for high-temperature porcelain firing, the gourd-shaped kiln mainly comprises the following parts: the dovetail wall, the kiln door, the front chamber, the rear chamber, the fuel replenishment and observation holes, and a chimney. The specific distribution of the kiln structure is shown in Fig. 1.

Model 1 is based on the dimensions of a reconstructed and fired gourd-shaped kiln structure in the Jingdezhen Ancient Kiln Folklore Expo Area. The kiln body is approximately 7.5 m long, divided into front and rear chambers. The front chamber is about 2.8 m long, while the rear chamber is about 4.7 m long. At the front end of the kiln, there are a kiln door, firebox, and ash pit. The kiln door is approximately 2.3 m high and 0.6 m wide. Inside the kiln door, there is a rectangular firebox approximately 1.2 m wide and 0.7 m long, with the ash pit approximately 1 m lower than the kiln bottom. At the rear of the gourd-shaped kiln, there is a square chimney approximately 8 m high. The entire kiln bed slopes from low at the front to high at the back, with a slope of 5 degrees. The specific distribution of the dimensions of Model 1’s kiln body structure is shown in Fig. 1.

Computational Domain Mesh

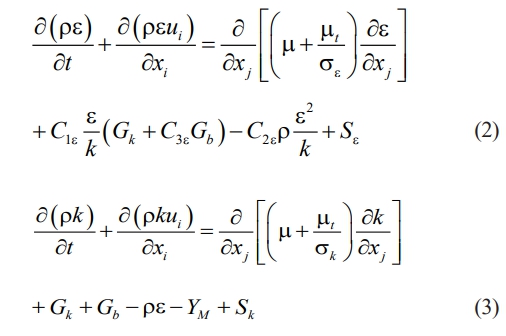

This study focuses on the numerical simulation of the temperature field and flow field inside the gourd-shaped kiln. To facilitate computation and ensure the reliability of the simulation results, the model of the gourd-shaped kiln was simplified by not including the firebox, ash pit, and chimney structures [32]. The simplified model of the gourd-shaped kiln is shown in Fig. 2.

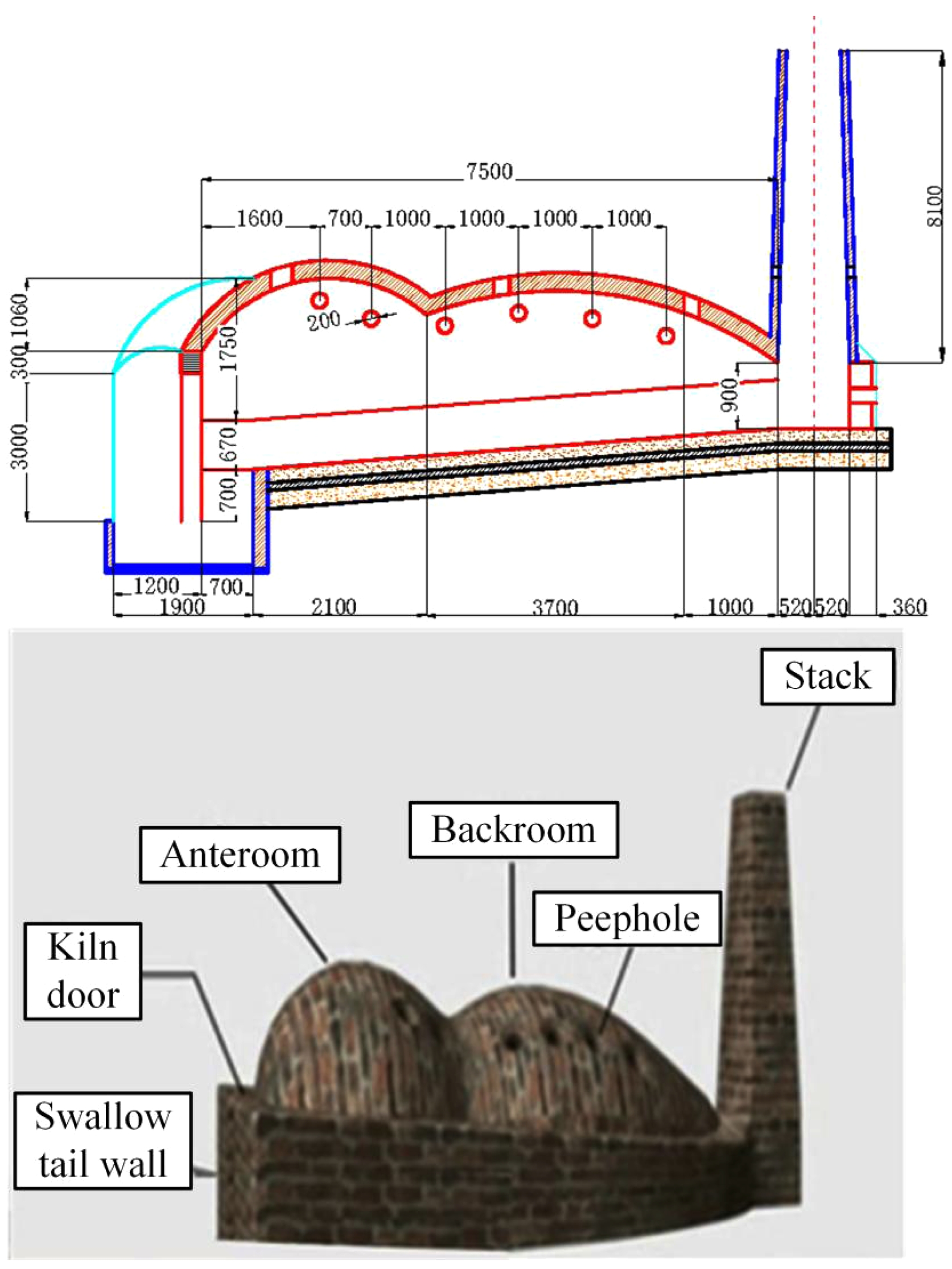

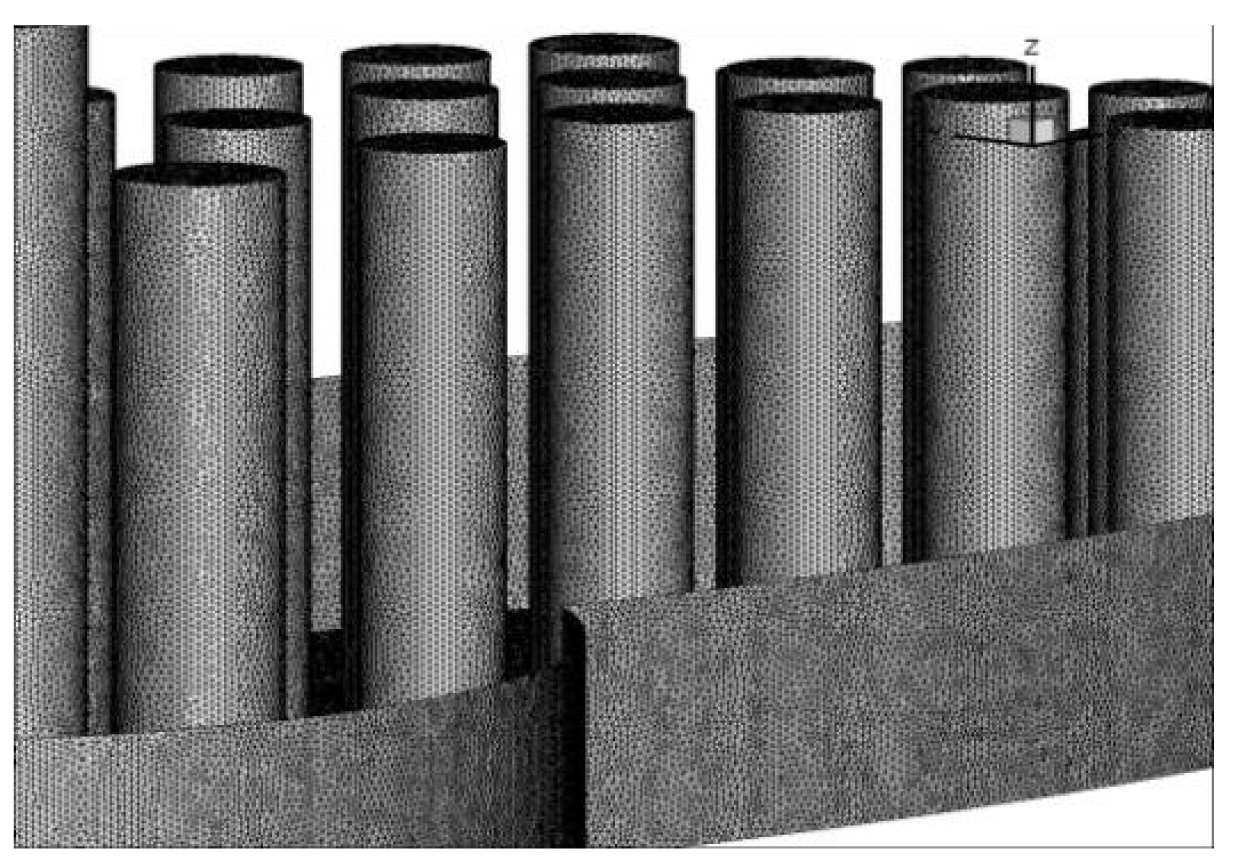

After simplifying the model, mesh division of the model was conducted using ICEM16.0 meshing software, employing unstructured mesh division with tetrahedral mesh elements as the main component. This method can better adapt to the complex geometric shapes inside the gourd-shaped kiln, ensuring the accuracy of the simulation results. The whole model is divided into unstructured meshes, mainly tetrahedral meshes, and the number of cells is about 1.24 million. The mesh model is shown in Fig. 3. Fig. 2 illustrates the simplified model of the gourd-shaped kiln, while Fig. 3 displays the model after mesh division. These illustrations clearly depict the structural features after simplification and the effect of mesh division, providing a reliable foundation for further numerical simulation studies.

Structured meshing presents certain difficulties in generating conformal structural meshes for objects with complex shapes. We can arrange a certain number of nodes according to the size and structure of the object area, and the arrangement of nodes follows a certain regular pattern, suitable for models with regular structural shapes. On the other hand, the distribution of nodes in unstructured meshes is random, without any structural characteristics, making it highly adaptable. Therefore, unstructured meshing is suitable for models with complex geometric shapes. With continuous optimization and upgrading of meshing software, certain criteria are applied to streamline and optimize the mesh during the process of generating unstructured meshes for models with complex shapes, ultimately improving the quality of the mesh.

Calculation Method

Due to the fact that the gas flow inside the gourd-shaped kiln involves steady-state three-dimensional turbulent flow with a swirling motion, the following assumptions were made to simplify the calculation: First, we applied a gas composition simplification. The mixed flue gas inside the kiln was considered as a single-component gas, neglecting the complexity of gas mixing. We also applied a radiative heat transfer neglect assumption, meaning the influence of radiative heat transfer was ignored, and only convective heat transfer was considered to simplify the calculation model.

To simulate turbulence, a standard two-equation turbulence model, namely the k−ε model, which is widely used and mature in ceramic kiln engineering calculations, was selected for turbulence calculation. This model can effectively simulate the vortex and energy dissipation processes in turbulent flow and is suitable for simulating complex flow inside kilns.

In order to perform turbulence simulation, it is necessary to establish the general form of the basic conservation equations, including the mass conservation equation, momentum conservation equation, and energy conservation equation. Below are the general partial differential conservation equations [33]:

where Φ is a common variable; Γ is the generalized diffusion coefficient; S is the generalized source term; and u, v, and w are the velocity components of the velocity of the mass in the microelement in the x, y, and z directions.

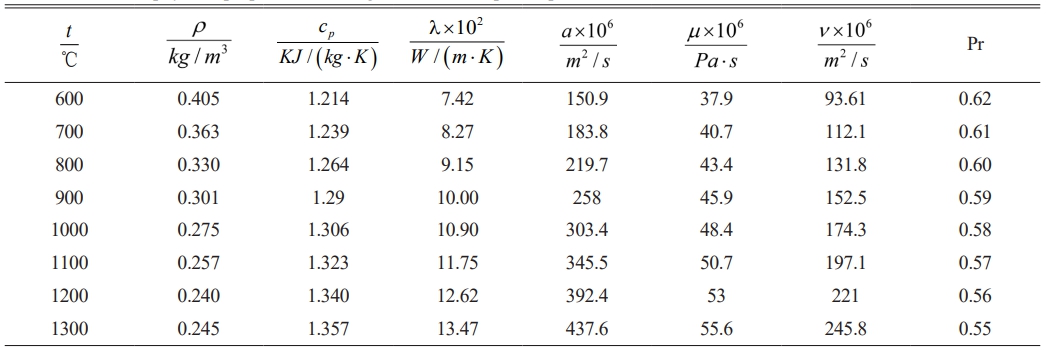

In the above three kiln body structure models, the flue gas inlet at the firebox is set as a velocity inlet. Based on the measured data from the gourd-shaped kiln re-firing site in the Jingdezhen Ancient Kiln Folklore Expo Area [31], the flue gas inlet velocity was set to 2 m/s, with a density of 1.41 kg/m³ and a temperature of 1330 °C (1603 K). The gas density used in this study was greater than standard gas density, which takes into account the chemical composition of the particular fuel and incomplete combustion. The flue gas outlet was set as a pressure outlet. The physical parameters of the flue gas are shown in Table 1. To ensure the accuracy of the simulation results and the values of the comparative analysis, the main simulation parameters of the three models were set to be the same, and subsequent numerical simulation calculations were conducted accordingly.

The k-ε turbulence model was one of the first turbulence models to be proposed, and it is widely used. It has been widely validated and recognized in industry and academia to have high reliability. The reasons for selecting this model for this paper mainly include its maturity and wide application, its computational cost and efficiency, its applicability and accuracy, its numerical stability and robustness, and its theoretical foundation and extensibility. When computing turbulence, the standard turbulence calculation model is utilized, where the turbulence kinetic energy equation (k equation) and the dissipation rate equation (ε equation) [34] can be expressed as follows:

Where cp is specific heat capacity, λ is thermal conductivity, α is thermal diffusivity, μ is dynamic viscosity, ν is kinematic viscosity, and Pr is Prandtl number.

|

Fig. 1 Structure diagram of gourd-shaped kiln. |

|

Fig. 2 Model diagram of gourd-shaped kiln. |

|

Fig. 3 Grid diagram of model |

|

Table 1 Thermal physical properties of flue gas under atmospheric pressure [29]. |

Kiln Temperature Field

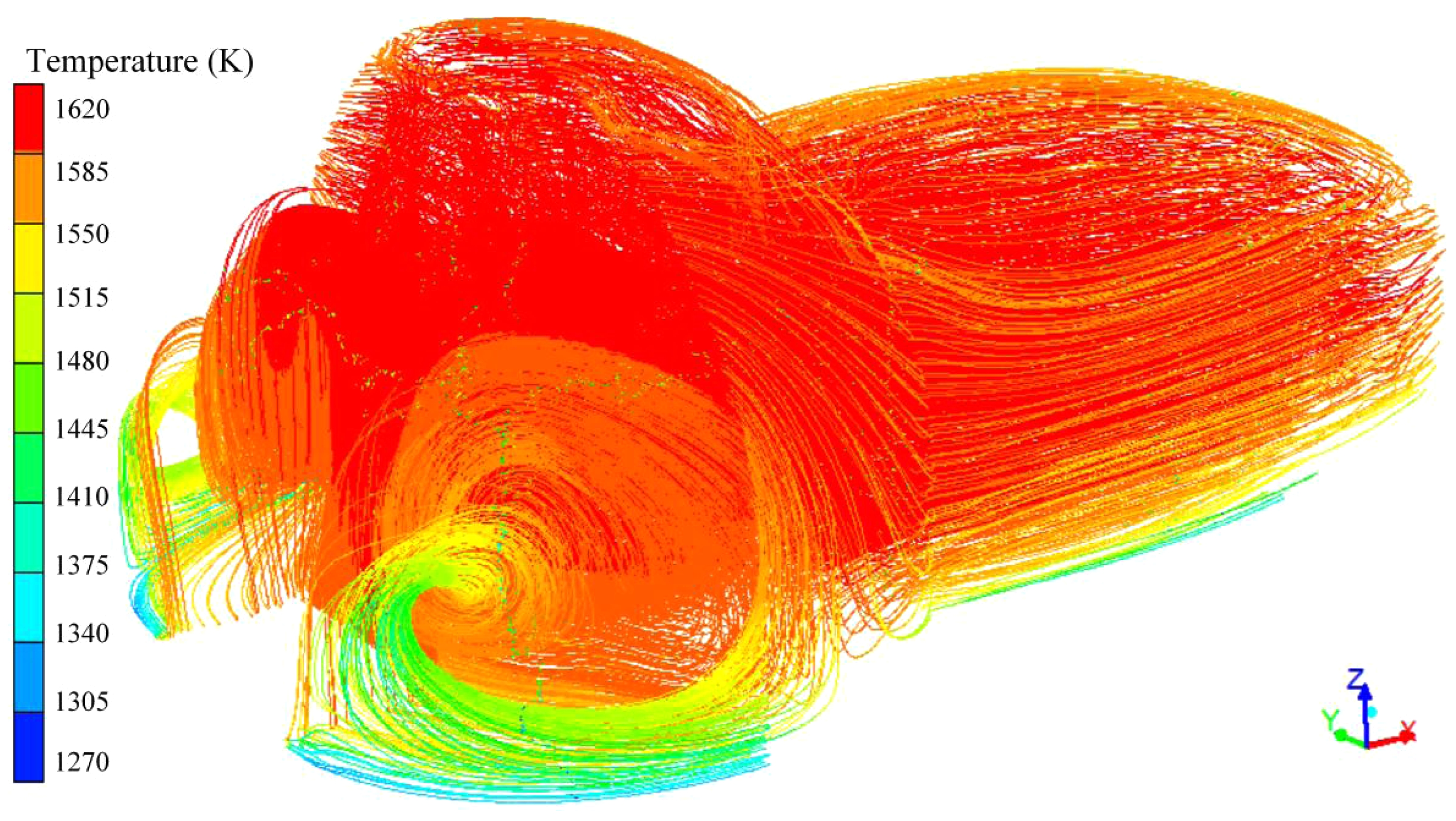

From the temperature streamlines in Fig. 4, it can be observed that the high-temperature flue gas entering the kiln initially rises to the top due to the buoyancy of hot air. Influenced by the unique gourd-shaped arch structure of the gourd-shaped kiln, a large amount of high-temperature flue gas gathers at the top of the front chamber, forming a high-temperature zone at the kiln top, with the highest temperature occurring at the arch of the front chamber. Due to the buoyancy of the high-temperature flue gas, it flows upward, causing the overall upper temperature of the kiln to be higher than the lower temperature, ultimately resulting in a temperature difference between the upper and lower parts of the kiln.

The presence of the constricted waist structure in the gourd-shaped kiln impedes the flow of flue gas into the rear chamber, causing the flue gas to form a semi-inverted flame-like flow inside the kiln. The increased turbulence of the flue gas and the formation of numerous flue gas eddies during the convective heat transfer process between the bricks and columns in the kiln lead to the occurrence of flue gas reflux. These phenomena not only help reduce the temperature difference between the upper and lower positions in the kiln but also enhance the convective heat transfer effect between the high-temperature flue gas and the bricks, increasing the residence time of the high-temperature flue gas in the front chamber. This, in turn, raises the firing temperature of the front chamber, serving the purpose of maintaining fire and raising temperature, thus further improving the firing quality of the products in the front chamber.

From the temperature distribution streamline diagram, it can also be observed that at the bottom of the kiln walls on both sides of the gourd-shaped kiln, due to the gourd-shaped structure causing dead spots in the flow of high-temperature flue gas and being far from the central high-temperature area of the kiln, there is a greater heat flow density from the kiln body to the external environment, resulting in the formation of some low-temperature areas. Although the gourd-shaped kiln has a ground-based kiln bed with a layer of refractory insulation material laid on the surface beforehand, during the firing process, heat continuously transfers to the ground, and likewise, heat is lost to the external environment through the kiln walls and roof, resulting in lower temperatures in certain areas on both sides of the kiln bottom, thereby creating a certain temperature gradient inside the kiln. However, with the rapid development of refractory insulation materials in recent years, heat dissipation from the kiln body has been significantly reduced.

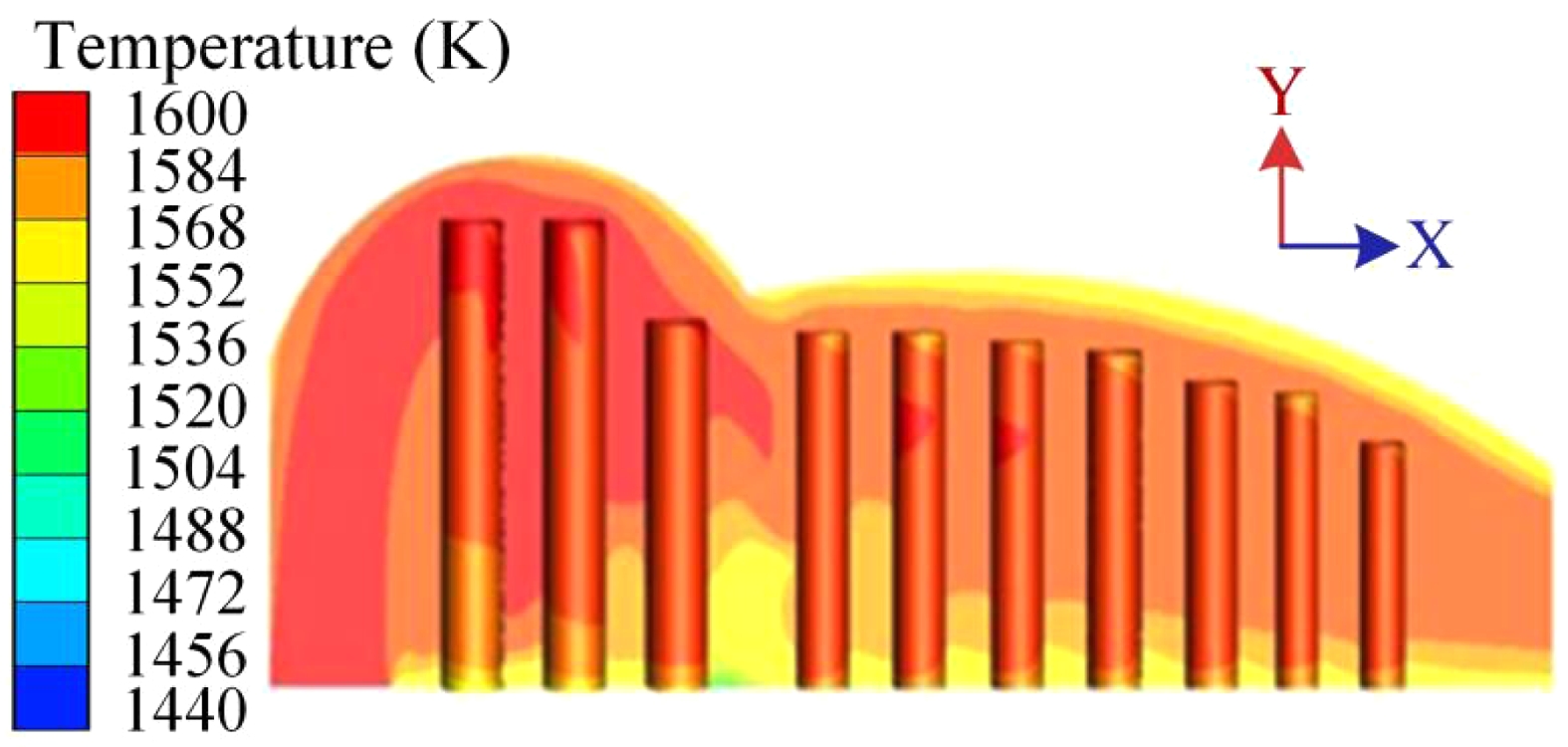

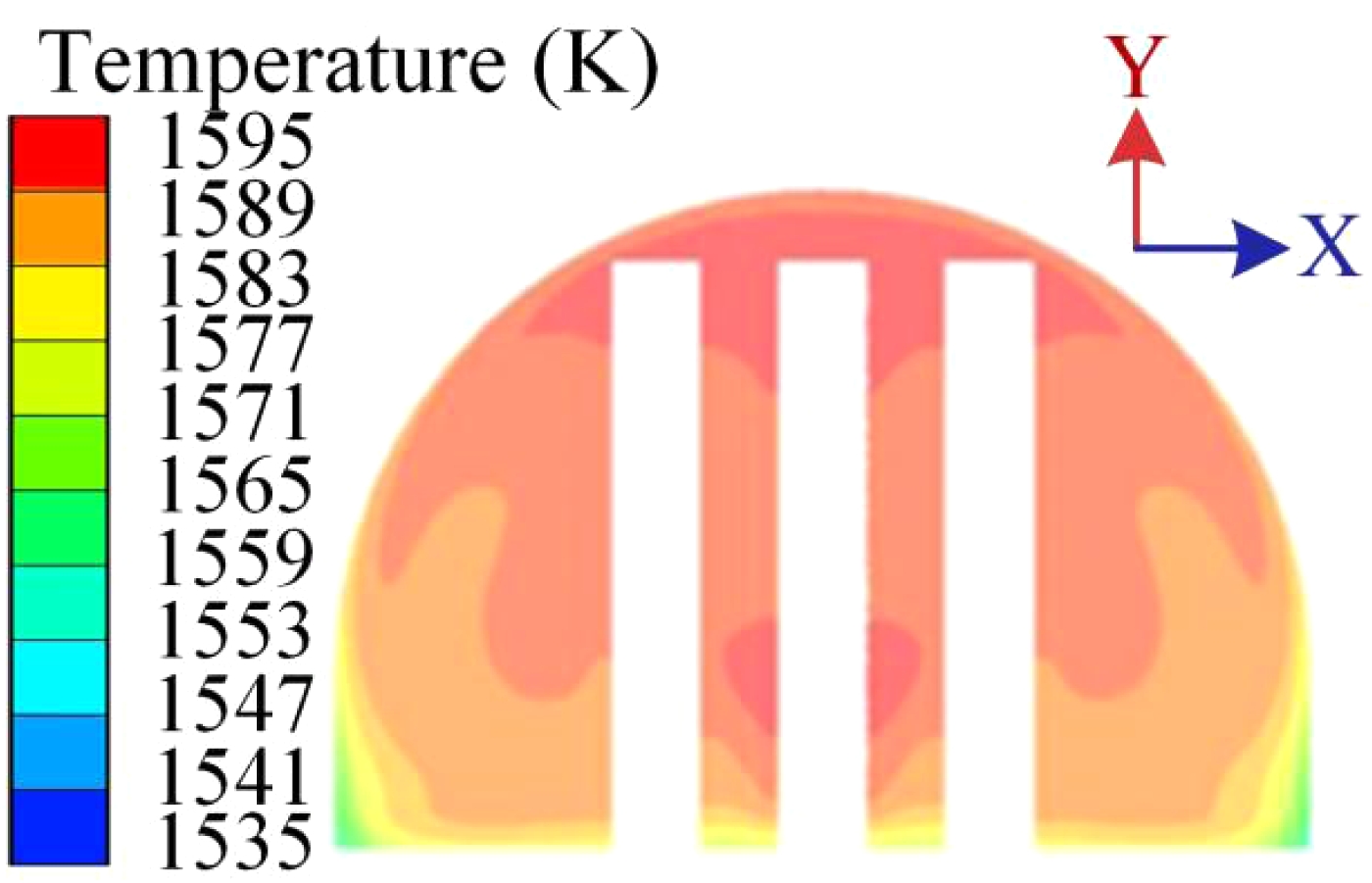

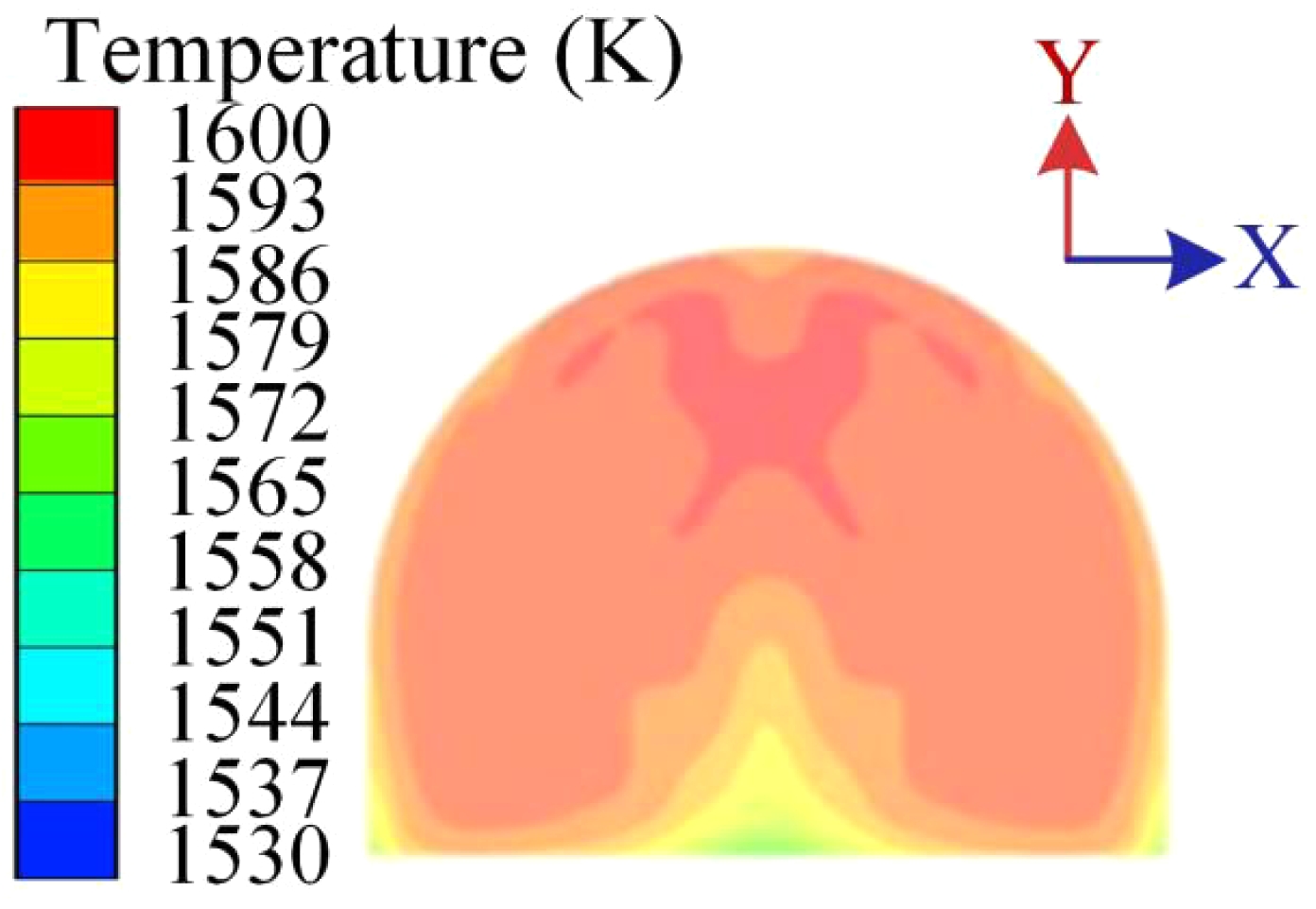

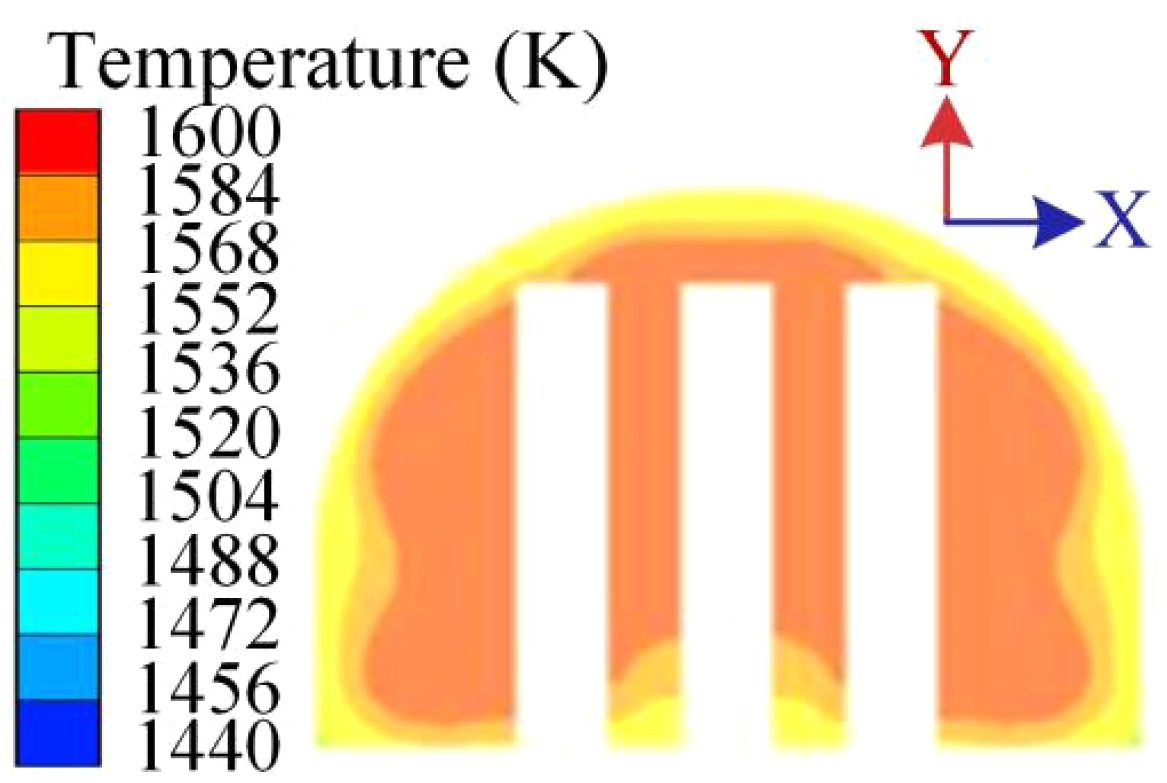

Fig. 5 illustrates the temperature distribution cloud map on the Y-axis symmetric plane of the kiln body, while Figs. 6, 7, and 8, respectively, present the temperature distribution in the middle of the front chamber, at the waist gate, and in the middle of the rear chamber of the gourd-shaped kiln. From these charts, it is evident that the high-temperature flue gas generated by fuel combustion flows into the front chamber at a certain velocity. Due to the large buoyancy of the high-temperature flue gas, it first rises to the top of the kiln. Influenced by the unique arch structure of the gourd-shaped kiln, a large amount of high-temperature flue gas tends to accumulate at the top of the front chamber. This results in the temperature being highest at the arch of the front chamber, where the maximum firing temperature inside the kiln can reach 1330 °C. The upper part of the front chamber exhibits a higher temperature than the lower part, with the temperature at the upper part of the front chamber’s bricks being 40 °C higher than the lower part. A similar situation exists in the rear chamber, where the temperature at the upper part of the bricks is 20 °C higher than the lower part.

Such an uneven temperature distribution may affect the firing process of ceramics, thus requiring further consideration and optimization. These temperature distribution characteristics provide important clues for a deeper understanding of the internal workings of the gourd-shaped kiln and also serve as beneficial references for adjusting the kiln structure and optimizing production processes.

The unique structure of the gourd-shaped kiln results in distinctive characteristics in its internal temperature field. The natural draft of the chimney at the rear of the kiln promotes the natural flow of high-temperature flue gas inside the kiln, playing a crucial role throughout the entire firing process. The high-temperature flue gas flows from the front chamber through the waist gate structure into the rear chamber. Subsequently, convective heat transfer, radiative heat transfer, and other processes occur in the bricks, kiln walls, and kiln bottom surfaces in the rear chamber, causing the temperature of the flue gas to gradually decrease. Eventually, relatively uniform temperature distribution areas are formed in certain regions.

The formation of such a temperature distribution is a crucial aspect of the entire firing process, directly impacting the quality and firing results of ceramic products. Therefore, in-depth research into the temperature field characteristics inside the gourd-shaped kiln and understanding the temperature distribution patterns are of significant importance for optimizing kiln structure design and improving production processes.

From the temperature distribution cloud map, it is evident that the temperature in the front chamber of the gourd-shaped kiln is significantly higher than that in the rear chamber. This temperature difference reaches a maximum of 60 °C, with the waist gate structure playing a crucial role in the overall temperature distribution. Particularly in the waist gate area, the temperature variation between the front and rear is most pronounced, with a maximum temperature difference of up to 40 °C. This phenomenon directly reflects the influence of the waist gate on the temperature field inside the kiln. The presence of the waist gate alters the flow path and velocity of the flue gas, making the temperature difference between the front and rear chambers more pronounced. This uneven temperature distribution has significant implications for the temperature control and firing results of ceramic products at different locations during the firing process.

This temperature distribution characteristic not only provides crucial guidance for kiln operators but also has profound implications for the improvement and innovation of ceramic manufacturing processes. Firstly, based on the temperature difference between the front and rear chambers, the manufacturing process can be more refined, allowing ceramic products in different areas to be fired under the most suitable temperature conditions, thus ensuring product quality and stability. Secondly, for ceramic products that require specific temperature environments, such as the sintering of glazes or the fixation of paintings, they can be placed in corresponding areas based on the characteristics of temperature distribution to enhance firing efficiency and product quality. Additionally, for the innovation and experimentation in ceramic craftsmanship, adjustments and optimizations can be made according to the temperature characteristics of the gourd-shaped kiln, exploring new firing methods and material combinations to create ceramics with greater creativity and artistic value.

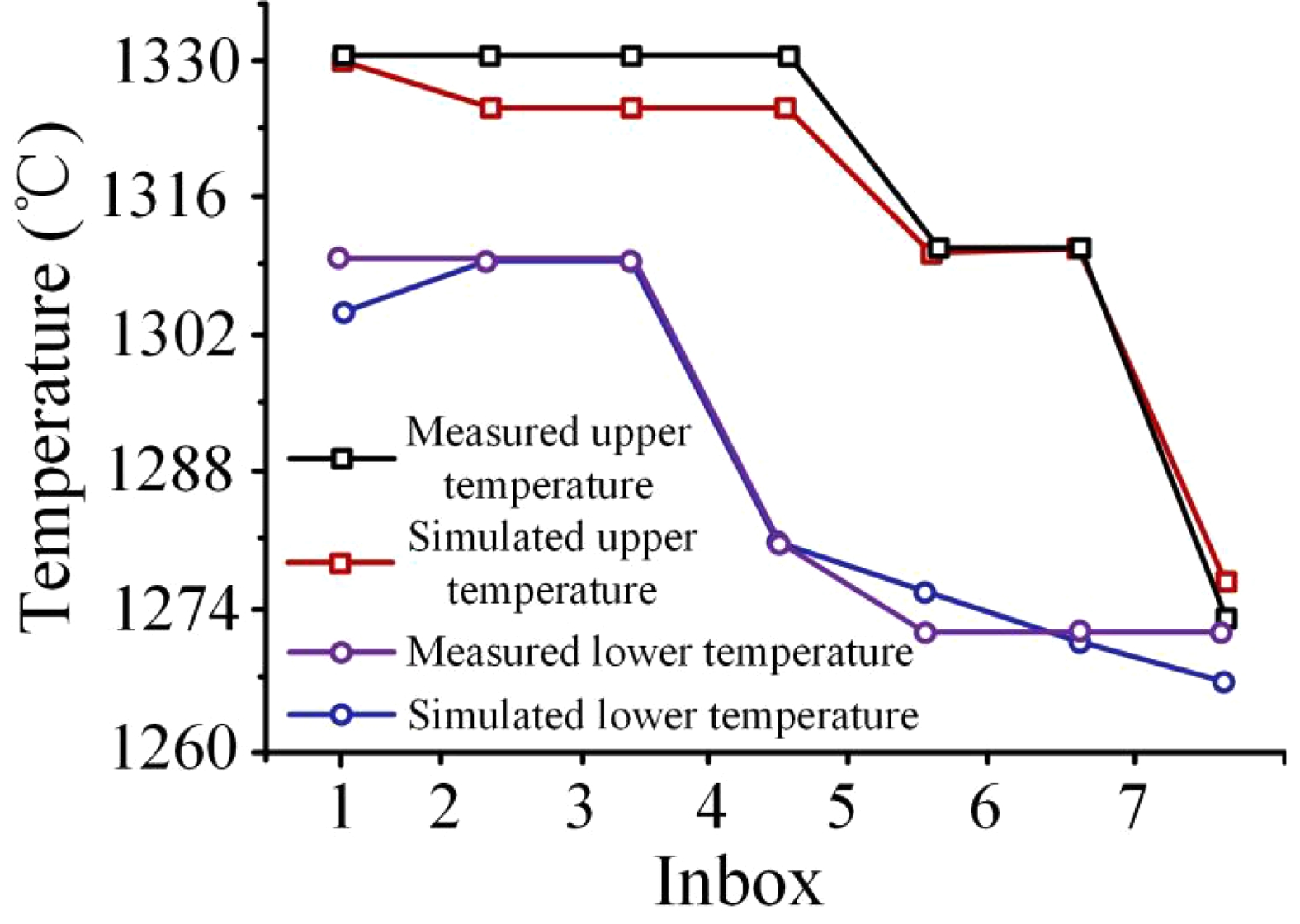

The data measured in the field firing test of the kiln were compared with the simulated data and analyzed. It can be seen that the two temperature curves fit very well, the maximum deviation is 0.75%, and the error is within the permissible range, which also proves the correctness of the model parameter settings. The entire firing cycle of the gourd-shaped kiln lasts approximately 20 h, with about 13 h for oxidation and the remaining 7 h for reduction to produce ceramics. During testing, thermocouples were used to measure the internal temperature of the kiln from observation ports every 30 min, starting from Port 1 to Port 6. A comparison and analysis between the actual measured temperature and the numerical simulation data were conducted to enhance the scientific rigor of the research results. According to the experimental data, it can be observed that the firing temperature inside the gourd-shaped kiln should be approximately between 1260 °C and 1330 °C. However, due to the unique structure of the gourd-shaped kiln and the influence of the stacking pattern of the ware on different kiln positions, the highest temperature measured varies at different locations. In this experiment, the highest firing temperature reached in the gourd-shaped kiln was 1330 °C, while the lowest temperature at the ground level was 1100 °C.

In Fig. 9, it is evident that the simulated temperature curve along the longitudinal direction of the gourd-shaped kiln’s middle section closely matches the measured temperature curve. This indicates that numerical simulation effectively replicates the variations in the internal temperature field of the gourd-shaped kiln during production. The close alignment between the measured and simulated temperature curves demonstrates a high level of agreement, suggesting that the numerical simulation results largely correspond to the real-world scenario. This consistency validates the accuracy and reliability of our simulation approach, providing a solid numerical simulation foundation for further investigation into the temperature variations within the gourd-shaped kiln.

Further comparison between the temperature and flow field parameters obtained from on-site experiments and numerical simulations revealed a high degree of agreement, with errors within acceptable limits. This validates the correctness of the model parameter settings, indicating that numerical simulation is an effective research method. These findings provide a reliable reference basis for subsequent studies on the structural evolution of gourd-shaped kilns, offering crucial support for further exploration of the variations in temperature and flow fields within the kiln. Additionally, they lay a theoretical foundation for a deeper understanding of the working principles of gourd-shaped kilns and the optimization of kiln body structures, contributing to the enhancement of kiln firing efficiency and product quality.

Kiln Velocity Field

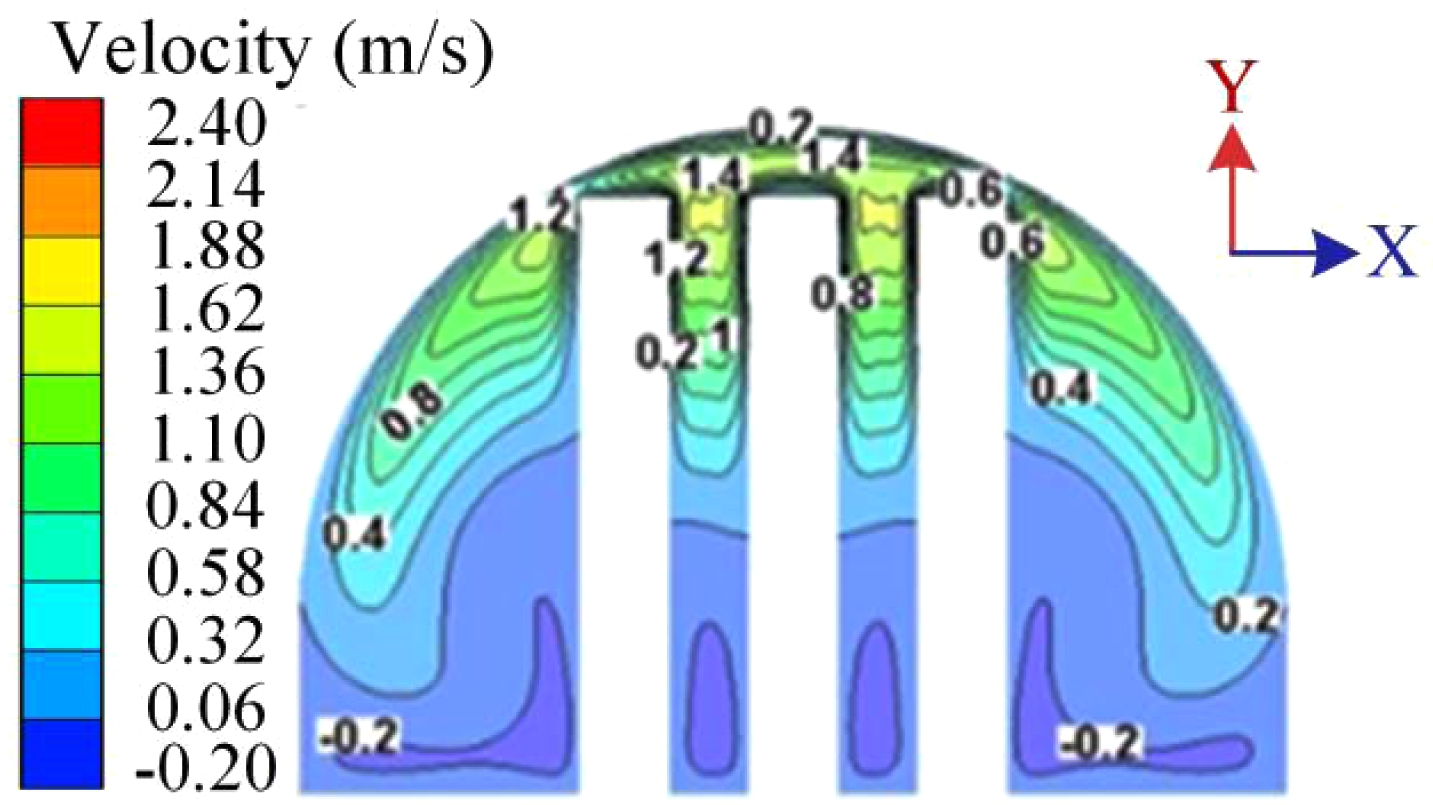

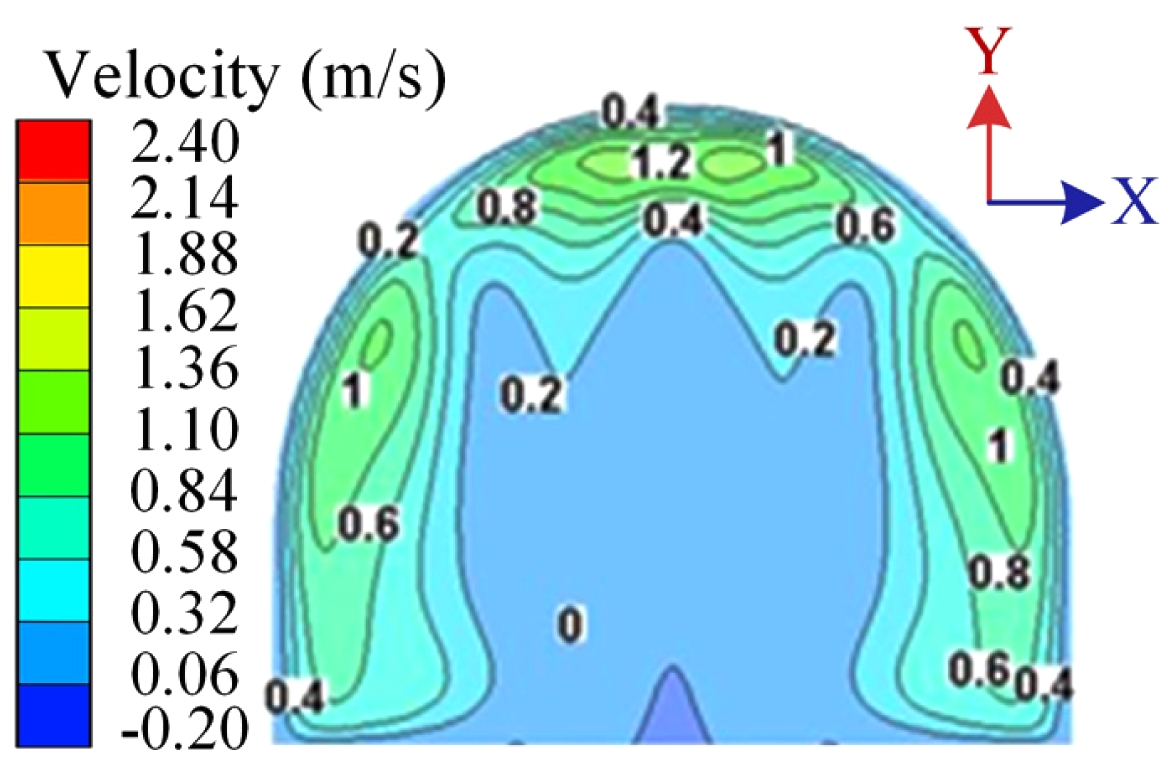

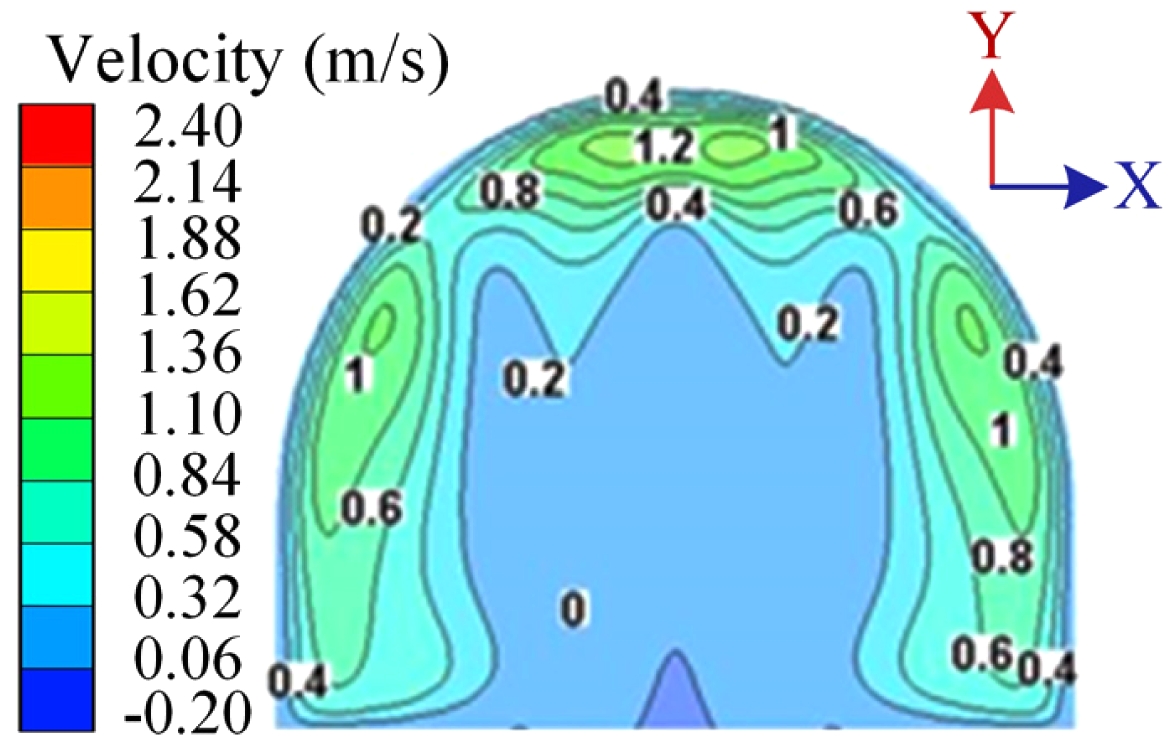

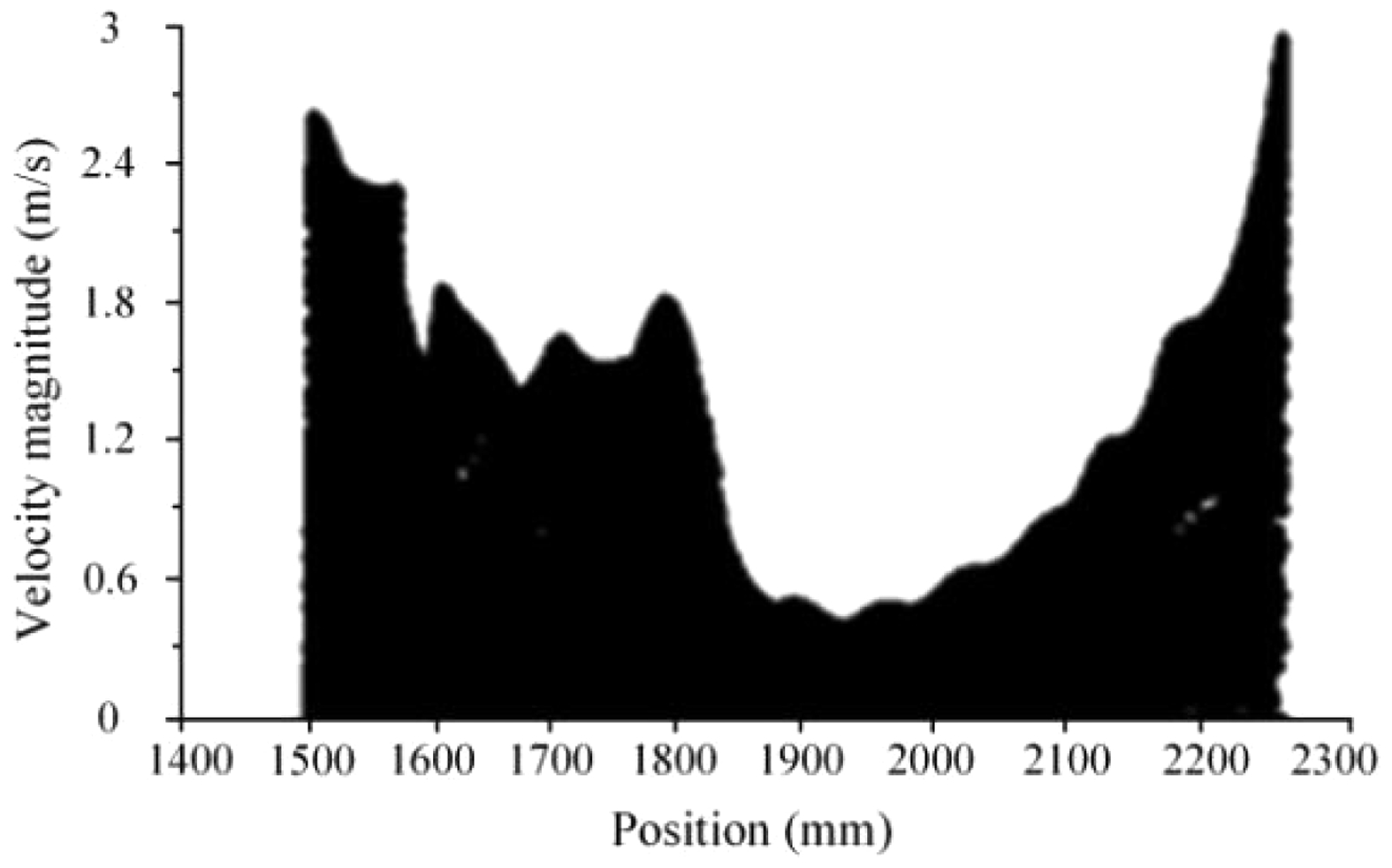

As shown in the velocity contour map, the unique front and rear chamber structure of the gourd-shaped kiln, along with the setting of the waist structure, make its internal flow field exceptionally complex. When high-temperature flue gas from the combustion chamber enters the kiln at a certain velocity, it first rises to the kiln top and then flows downward along the kiln wall. At the kiln top, the flow velocity of the flue gas reaches its maximum value, around 2.3 m/s, forming an inverted flame-like flow pattern throughout the kiln. This inverted flame flow leads to the formation of varying degrees of vortices between the box-bowl passages and even causes some degree of flue gas backflow in the front chamber. This complex flow pattern results in differences in flow velocity between the upper and lower parts of the kiln, with the velocity in the upper part being approximately 1.4 m/s, while in the lower part, it is only 0.4 m/s. At the bottom, there may even be flue gas backflow, causing a reversal in flow direction. Under such circumstances, turbulent fluctuations intensify, increasing the disorderliness of the airflow and, consequently, enhancing the heat transfer effect between the high-temperature flue gas and the box-bowl pillars.

Therefore, the higher firing temperature in the front chamber results in a superior quality of the fired products. These complex flow characteristics provide a deep understanding of the formation of the internal temperature field and the firing process in the gourd-shaped kiln while also offering important references for optimizing kiln structure and firing techniques. Influenced by its internal structure, as indicated by the velocity distribution maps at various positions along the length of the kiln, the horizontal movement of the gas main stream continues to strengthen. The setting of the waist structure in the middle of the kiln reduces the cross-sectional area for gas flow, and its effect is twofold: on one hand, it reduces the amount of high-temperature flue gas from the front chamber entering the rear chamber, playing a certain blocking role; on the other hand, the reduced flow area through the waist structure leads to an increase in flow velocity, with flue gas velocities reaching up to 1.5 m/s, thereby enhancing the turbulence of flue gas flow, strengthening convective heat transfer between the flue gas and the box-bowl, and improving the firing speed of the products (Figs. 10-13).

As the flue gas passes through the waist structure of the kiln, it can be clearly observed that the flow velocity of the flue gas directly decreases to 0.5 m/s. Subsequently, as the flue gas enters the rear chamber, the length of the rear chamber increases and the flow area enlarges, resulting in a corresponding decrease in flow velocity. This design increases the heat exchange time between the flue gas in the rear chamber and the products, raises the firing temperature, and reduces the temperature difference within the kiln, thereby enhancing the quality of the fired products. Additionally, in the tail section of the gourd-shaped kiln’s rear chamber, due to the reduced outlet area for the flue gas and the natural draft force of the chimney, the flue gas flow velocity increases. The flue gas flow velocity near the tail of the kiln body can reach up to 2.5 m/s. This structural design further promotes the discharge of flue gas, ensuring the stability of the flow field, and contributes to maintaining the continuity and stability of the firing process.

The uneven lengths of the front and rear chambers of the gourd-shaped kiln are designed to adjust the lengths of the chambers and the position of the waist structure in between, aiming to maintain high-temperature zones and accommodate a greater variety of ceramic products. The waist structure in the middle divides the kiln space into two smaller front and rear chambers. This design has several significant features: firstly, it can enhance the firing temperature in the front chamber, thereby improving the quality of the products; secondly, it can regulate the temperature and atmosphere inside the kiln, making the firing system more flexible and enhancing product quality.

However, the waist structure in the middle also impedes the flow of high-temperature flue gas into the rear chamber. While it prolongs the residence time of the high-temperature flue gas in the front chamber, the hindrance to the flow of flue gas by this structure results in a significant temperature difference between the front and rear chambers, with the rear chamber being cooler. Therefore, the rear chamber is more suitable for firing small pieces or thin-walled products. Additionally, the gourd-shaped kiln structure also poses certain difficulties for the construction and maintenance of the kiln in the later stages.

|

Fig. 4 Temperature flow diagram of flue gas in the kiln. |

|

Fig. 5 Cloud diagram of the temperature distribution of the Y-axis symmetric plane of the kiln body. |

|

Fig. 6 Temperature distribution profile in the middle of the front chamber. |

|

Fig. 7 Temperature distribution diagram of waist section of calabash kiln. |

|

Fig. 8 Temperature distribution profile in the middle of the rear chamber. |

|

Fig. 9 Curve of simulated temperature and measured temperature distribution. |

|

Fig. 10 Velocity distribution profile in the middle of the front chamber. |

|

Fig. 11 Velocity distribution diagram of waist section of gourdshaped kiln. |

|

Fig. 12 Velocity distribution profile in the middle of the rear chamber. |

|

Fig. 13 Velocity distribution diagram of x direction of Y axis symmetric surface along the direction of kiln. |

By consulting historical records and data from archaeological sites and carrying out on-site measurements of the reconstructed gourd-shaped kiln in Jingdezhen, basic structural data of the gourd-shaped kiln were collected. A three-dimensional structural computational model was established, and numerical methods were employed to study the temperature field and flow field inside the gourd-shaped kiln. The CFD analysis revealed the factors involved in the structural evolution of the gourd-shaped kiln from a thermo-engineering point of view, providing reference value for its future design optimization. The following conclusions were drawn:

(1) Firing temperature and applicability: The firing temperature of the gourd-shaped kiln can reach up to 1330 °C, making it suitable for the small-scale firing of ceramic products. The temperature difference between the front and rear chambers can reach 60 °C, with the largest temperature difference of 40 °C observed in the area of the waist section. Due to the uneven temperature distribution, the front chamber is suitable for firing high-temperature products, while the rear chamber is suitable for low-temperature products.

(2) Impact of structure on temperature field: The intermediate waist section structure contributes to the uniform distribution of temperature within the kiln, resulting in a smaller temperature difference between the front and rear chambers. The temperature in the upper part of the front chamber’s niches is 40 °C higher than that in the lower part, while in the rear chamber, the temperature in the upper part of the niches is 20 °C higher than that in the lower part, indicating a uniform temperature distribution inside the kiln.

(3) Complexity of internal flow field: The gas velocity at the kiln’s top reaches a maximum of 2.3 m/s, forming a flame reversal flow pattern, with a reverse flow velocity observed at the bottom. The waist section structure reduces the gas velocity from 1.5 m/s to 0.5 m/s, prolonging the gas residence time inside the kiln, elevating the firing temperature, reducing temperature differentials, and enhancing product quality.

In future work, we will conduct a more comprehensive thermodynamic analysis of the gourd-shaped kiln and examine the intrinsic mechanisms of its structural evolution in the context of the modern kiln.

- 1. M. Li, G. Hu, and Y. Wu, China Ceram. Ind. 18[01] (2011) 39-42.

- 2. W. Li, Z. Li, W. han, S. Tan, S. Yan, D. Wang, and S. Yang, Phys. Fluids. 35[12] (2023) 125145.

-

- 3. W. Li, Z. Li, W. Han, Y. Li, S. Yan, Q. Zhao, and Z. Gu, Phys. Fluids. 35[5] (2023) 052005.

-

- 4. Z. Ren, W. Zhou, and D. Li, Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 236[13] (2022) 7166-7178.

-

- 5. J. Tong, Z. Shao, and Y. Fan, China Ceram. [01] (1997) 11-13.

- 6. M. Fang, J. Hua, and L. Yang, J. Northeast For. Univ. 47[06] (2019) 65-69.

- 7. X. Li, Q. Guo, and Q. Yang, Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 35[11] (2016) 3803-3807+3818.

- 8. S. Yan and F. Gao, Shandong Chem. Ind. 47[04] (2018) 83-88.

- 9. X. Zeng, X. Wang, and P. Li, J. Ceram. 40[01] (2019) 79-83.

- 10. X. Pan, H. Qiu, and R. Lai, J. Ceram. 36[04] (2015) 429-433.

- 11. M. Wang, S. Li, X. Lv, S. Zhang, Z. Gong, and T. Lou, Multipurp. Util. Miner. Resour. 44[02] (2023) 52-55.

- 12. C. Lu, S. Yan, J. Can, and L. He, Multipurp. Util. Miner. Resour. 42[01] (2021) 134-139.

- 13. W. Jin, F. Du, and Z. Liu, Shandong Chem. Ind. 40[09] (2011) 26-29.

- 14. T. Geng and Q. Ren, Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc 30[02] (2011) 394-397.

- 15. H. Yang, Q. Chen, K. Xu, and C. Zhu, CIESC J. 70[12] (2019) 4608-4616.

-

- 16. M. Wang, L. Che, C. Shi, H. Yuan, and Y. Liu, Refractories. 57[6] (2023) 504-507.

- 17. R. Wen, Y. Zhang, and X. Fu, Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 35[04] (2023) 1-10.

- 18. R. Zhang, J. Ceram. 37[06] (2016) 718-723.

- 19. B. Delpech, B. Axcell, and H. Jouhara, Energy. 170 (2019) 636-651.

-

- 20. N. Akram, U.M. Moazzam, M.H. Ali, A. Ajaz, A. Saleem, M. Kilic, and A. Mobeen, Therm. Sci. 22[2] (2018) 1089-1098.

-

- 21. D. Brough, A. Mezquit, S. Ferrer, C. Segarra, A. Chauhan, S. Almahmoud, N. Khordehgah, L. Ahmad, D. Middleton, H.I. Sewell, and S. Ferrer, Energy. 208[2] (2020) 118325.

-

- 22. S. Mun, Y.T. Kim, K.B. Shim, and S.C. Yi, J. Ceram. Process Res. 10[3] (2009) 401-407.

-

- 23. S.C. Yi and K.H. Auh, J. Ceram. Process Res. 3[3] (2002) 96-100.

- 24. S. Ahmad and Y. Iqbal, J. Ceram. Process Res. 17[4] (2016) 373-379.

-

- 25. Q. Feng, K. Li, and X. Gong, China. Ceram. [04] (2006) 26-30.

- 26. G. Liu, G. Cui, and B. Xie, J. Eng. Therm. Energy Power. 34[06] (2019) 100-108.

- 27. N. Cheng, J. Sun, and W. Gui, Control and. Decision. 39[05] (2024) 1550-1556.

- 28. L. Zhu, S. Lyu, S. Sun, S. Yu, C. Yang, and X. Sun, Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 39[9] (2020) 3543-3549.

-

- 29. L. Y. Li, J. J. Han, H. J. Lin, K. W. Hu, J. Xie, and X.J. Zhao, Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 38[06] (2019) 1674-1680.

- 30. Y. Sun, “Numerical simulation of combustion characteristics of alternative fuels in cement kilns,” Ph.D. dissertation, Anhui University of Technology: Hefei, China, (2019).

- 31. J. Tong, Q. Feng, and H. Wang, China Ceram. [05] (2006) 27-31.

- 32. X. Pan, X. Qu, and L. Lu, China Ceram. 52[11] (2016) 38-42.

- 33. L. Lu, Q. Feng, and X. Gong, China Ceram. [03] (2008) 25-28+31.

- 34. S. Yang, W. Tao, in “Heat Transfer” (Higher Education Press, 2006) p.215.

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 940-949

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.940

- Received on Jul 3, 2025

- Revised on Jul 26, 2025

- Accepted on Aug 29, 2025

Services

Services

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Junming Wu

-

School of Archaeology and Museology, Jingdezhen Ceramic University, Jingdezhen 333403, China

Tel : +8613879839817 - E-mail: woshiwxb@126.com

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.