- Sintering behavior and properties of Mo-Cu composites produced by spark plasma sintering

Yu-gyun Parka,b, Min-hyeok Yanga,b, Yeong-jung Kima,b and Hyun-kuk Parka,*

aPurpose-based Mobility Group, Korea Institute of Industrial technology, Gwangju 61012, Republic of Korea

bDivision of Advanced Materials Engineering, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Republic of KoreaThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The Mo-Cu composites containing 10-40 wt.% Cu were fabricated by subjecting Mo and Cu powders to high energy ball milling for 15 hrs at 200 rpm, followed by spark plasma sintering at 950 °C under 60 MPa. The synthesized powders were sintered using SPS, resulting in a gradual increase in relative density from 82.8% for Mo-10Cu to 90.1% for Mo-40Cu with increasing Cu content. X-ray diffraction confirmed that only Mo and Cu phases were present in all sintered samples. Microstructural analysis revealed a transition from isolated Cu regions in a Mo matrix at low Cu content to a continuous Cu matrix with dispersed Mo particles at high Cu content. The thermal conductivity of the composites increased from 122.8 to 158.8 W/m·K as the Cu content increased, while the Vickers hardness decreased from 591.2 to 395.2 Hv due to the increase in the volume fraction of Cu, which has a lower hardness compared to Mo.

Keywords: Mo-Cu, High energy ball milling, Spark plasma sintering, Mechanical property, Thermal property.

The rapid advancement in electronic devices has intensified the demand for effective thermal management materials due to the heat generated during operation. Inadequate heat dissipation can lead to performance degradation and reduced lifespan of electronic components. Therefore, materials with high thermal conductivity and low thermal expansion coefficients are essential for ensuring stability and efficiency in electronic systems [1-5].

Copper (Cu) is extensively utilized in heat sinks and electronic packaging due to its excellent thermal conductivity (401 W/m·K), electrical conductivity, and formability. However, its relatively high coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE, 16.5 μm/m·K) and low mechanical strength limit its application in high-power microwave devices, vacuum technologies, and heat dissipation systems that require dimensional stability [6,7].

Molybdenum (Mo), a refractory metal with a body-centered cubic (bcc) structure, exhibits high melting point (2623 °C), low CTE (4.8 μm/m·K), high elastic modulus, and good strength at elevated temperatures. Despite these advantageous properties, Mo's relatively low thermal conductivity (138 W/m·K) restricts its standalone use in thermal management applications [8].

Mo-Cu composites present a promising solution by combining the desirable properties of both constituent materials: Mo provides high strength and low thermal expansion, while Cu contributes superior thermal conductivity [9]. However, the fabrication of Mo-Cu composites faces challenges due to the immiscibility of Mo and Cu in both solid and liquid states, which complicates alloying through conventional casting or liquid metallurgy methods [10].

Several processing techniques have been explored for fabricating Mo-Cu composites, including powder metallurgy [11], infiltration [12], and mechanical alloying [13]. Among these, high energy ball milling (HEBM) has emerged as an effective non-equilibrium processing technique for producing fine powders with nanocrystalline structures through repeated welding, fracturing, and rewelding processes under high impact energy. This method increases crystal defects such as dislocations and grain boundaries while enabling higher solid solubility in immiscible systems like Mo-Cu [14].

Spark plasma sintering (SPS) has proven to be an effective consolidation method for fabricating dense materials at relatively low temperatures with short processing times [15-17]. The SPS process employs pulsed direct current along with uniaxial pressure to facilitate rapid heating and enhanced densification. The rapid heating rates and short dwell times in SPS minimize grain growth, making it particularly suitable for preserving the nanostructured features produced by high energy ball milling.

In this study, Mo-Cu composites with varying Cu content (10-40 wt.%) were fabricated using high energy ball milling followed by spark plasma sintering. The influence of Cu content on the microstructure, density, hardness, and thermal conductivity of the sintered composites was systematically investigated. The correlation between composition, microstructure, and properties was analyzed to optimize Mo-Cu composites for potential applications in thermal management systems.

Mo powder (JMC Co., purity >99.93%, particle size <3 μm) and Cu powder (Alco Engineering Co., purity >99.9%, particle size <30 μm) were used as raw materials. The powders were weighed at weight ratios of 90:10, 80:20, 70:30, and 60:40 (Mo:Cu) and milled using a high energy ball mill (Pulverisette-5, Fritsch) for 15 hrs at a rotational speed of 200 rpm under an argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation. Stainless steel balls with a diameter of 10 mm were used with a ball-to-powder weight ratio of 10:1. After milling, the powders were dried in a vacuum oven at 100 °C for 12 hrs.

The energy transfer mechanism in the high-energy ball milling of Mo-Cu powders was quantified using collision kinetics and power consumption models. A single 10 mm stainless steel ball (mass = 4.08 g) generated an impact energy of:

where the collision velocity was calculated as 3.77 m/s at 200 rpm. With 122 balls undergoing 6.67 collisions per second, the total energy transfer rate reached 23.6 J/s. The specific energy input for 50 g of powder after 15 hrs milling was:

within the critical range (0.5–2 MJ/g) required for mechanical alloying. The low collision efficiency (≈1.8%) aligns with typical energy losses due to friction and heat dissipation in planetary mills.

The ball-to-powder ratio (BPR) of 10:1 ensured sufficient impact energy while avoiding overfilling. At 200 rpm, the centrifugal acceleration reached:

inducing a cascading motion regime ideal for plastic deformation without excessive temperature rise. This balanced the refinement of Cu particles (initial size: <30 μm) and the dispersion of Mo particles (3 μm) into a lamellar composite structure.

The milled powders were filled in a graphite molds (outer diameter: 40 mmØ, inner diameter: 20 mmØ, height: 50 mmT) and then the upper and lower parts were blocked with a graphite punch. The SPS process was conducted using an SPS system (SPS-9.40 MK-III, Sumitomo Heavy Industries). Initially, a pressure of 10 MPa was applied, and the temperature was increased to 600 °C at a heating rate of 50 °C/min and maintained for 1 min. Subsequently, the pressure was increased to 60 MPa, and the temperature was raised to 950 °C at the same heating rate and held for 5 min. The selection of 950 °C was based on a balance of densification efficiency and microstructural stability, determined through preliminary experiments conducted at 900 °C, 1000 °C, and 1050°C. At temperatures of 1000 °C and 1050 °C (approaching Cu's melting point of 1085 °C ), the copper phase began to exhibit signs of localized melting. Sintering at or above 1000 °C was not considered suitable. Conversely, at 900 °C, the shrinkage analysis indicated that continuous shrinkage was still occurring at the end of the thermal cycle. This suggested that 900 °C was insufficient for achieving complete densification and full microstructural development. Consequently, 950 °C was established as the optimal sintering temperature. After sintering, the samples were cooled to 200 °C in the chamber before the pressure was released.

The relative density of the sintered samples was measured using the Archimedes method. X-ray diffraction (XRD, X'pert PRO, Malvern Panalytical) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm) was performed to identify the phase composition of both milled powders and sintered samples. The microstructure was examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, JSM-7001F, JEOL) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

The Vickers hardness was measured using a Vickers hardness tester (HV-100, Mitutoyo) under a load of 5 kgf with a dwell time of 15 s. The hardness values were calculated using Eq. (4):

where P is the applied load (kgf) and d is the diagonal length of the indentation (mm).

The thermal properties were measured using a laser flash analyzer (LFA447, NETZSCH Geraetebau GmbH) and a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC8000, PerkinElmer). The thermal conductivity (λ) was calculated using Eq. (5):

where α is the thermal diffusivity (mm²/s), Cp is the specific heat capacity (J/g·K), and ρ is the density (g/cm³).

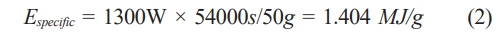

Fig. 1 shows the changes in the shrinkage displacement of the sintered body as a function of sintering temperature and time. The sintering temperature curve shown in Fig. 1 represents the actual, real-time temperature measured during the Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) cycle. This measurement was obtained using a K-type shielded thermocouple. This thermocouple was positioned within a dedicated channel located in the wall of the graphite die, immediately adjacent to the powder. The sintering behavior of Mo-Cu composites exhibits two distinct shrinkage stages during the SPS process [18]. In Stage I, occurring at approximately 200-600 °C, initial shrinkage is observed due to particle rearrangement and neck formation between particles. In Stage II, at temperatures above 600 °C, significant densification takes place through neck growth, pore elimination, and lattice diffusion mechanisms. As the Cu content increased from 10 to 40 wt.%, it showed a large shrinkage at the shrinkage temperature. This behavior can be attributed to low melting point of copper (1085 °C) compared to Mo (2623 °C), which enhances atomic diffusion during sintering. The higher Cu content facilitates densification through liquid phase sintering mechanisms, where Cu acts as a sintering aid by forming liquid phases that fill pores and enhance mass transport. The relative density increases from 82.8 for Mo-10Cu to 90.1% for Mo-40Cu. This trend indicates that higher Cu content promotes densification during the SPS process, primarily due to better flowability of Cu at high temperatures. Similar observations have been reported by Park et al. [19] and Kim et al. [20] in their studies on sintering of metal matrix composites. The densification behavior of Mo-Cu composites can be further understood by examining the microstructural evolution during the sintering process. The first stage of densification (200-600 °C) is dominated by particle rearrangement and surface diffusion mechanisms, which lead to the formation of necks between adjacent particles. The applied pressure during SPS enhances this rearrangement by overcoming particle friction and promoting closer packing. As the temperature increases above 600 °C in the second stage, volume diffusion becomes the predominant mechanism for mass transport, resulting in significant densification. The applied pressure further facilitates the reduction of pores and enhances densification. For Mo-Cu composites, the densification behavior is strongly influenced by the Cu content due to the substantial difference in the melting points of Mo and Cu. At 950 °C, Cu approaches its melting point (1085 °C), leading to enhanced atomic mobility and diffusion rates, while Mo remains in the solid state (melting point 2623 °C). This temperature differential creates a pseudo-liquid phase sintering condition, where Cu functions as a sintering aid by providing fast diffusion paths through grain boundaries and surfaces. The relative density measurements reveal a clear correlation with Cu content, increasing from 82.8% for Mo-10Cu to 90.1% for Mo-40Cu. This trend is consistent with studies on similar refractory metal-copper systems such as W-Cu, where higher Cu content typically results in better densification [21].

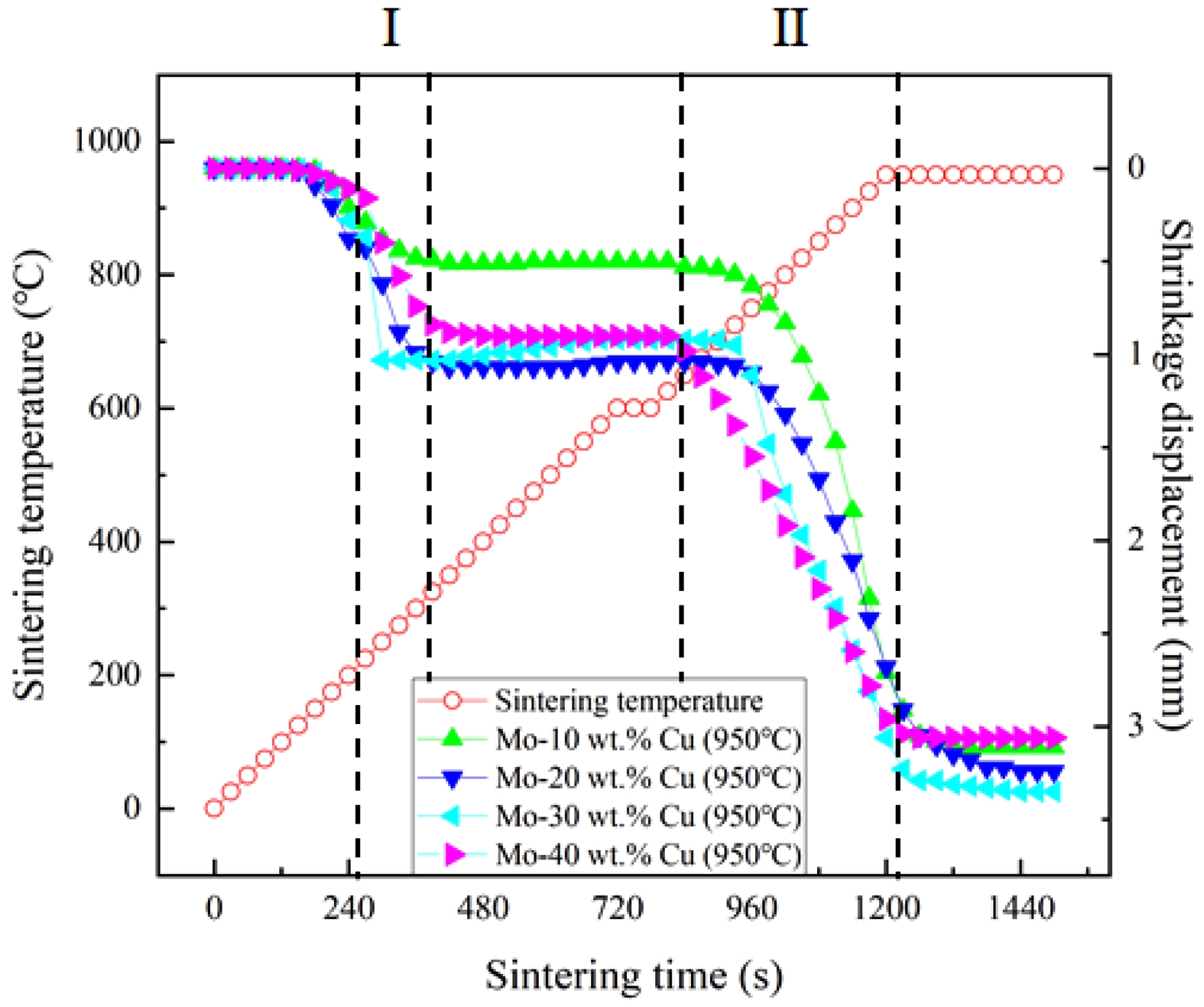

Fig. 2 shows the results of phase analysis before and after sintering of sintered bodies fabricated by the spark plasma sintering process. XRD patterns of the milled powders show only Mo and Cu peaks, confirming that no chemical reaction occurs during the milling process. The broadening of the diffraction peaks can be attributed to the reduction in crystallite size and the increase in lattice strain during high energy ball milling. The XRD patterns of the sintered composites also exhibit only Mo and Cu peaks, indicating that no secondary phases form during sintering at 950 °C. This is consistent with the Mo-Cu binary phase diagram [22], which shows negligible solid solubility and no intermetallic compounds. The intensity of Cu peaks increases with Cu content, reflecting the higher proportion of Cu in the composites. Additionally, the sharpening of peaks compared to the milled powders suggests grain growth during sintering, which is typical in thermal consolidation processes. The preservation of the individual Mo and Cu phases without the formation of intermetallic compounds or solid solutions, even after high energy ball milling and SPS, is noteworthy. This phase stability can be explained by the thermodynamic immiscibility of Mo and Cu, which have a positive enthalpy of mixing and show limited mutual solubility even at elevated temperatures [23]. The binary phase diagram indicates that the maximum solubility of Cu in Mo is approximately 0.1 at.% at the eutectic temperature, while the solubility of Mo in Cu is even lower. This immiscibility is advantageous for Mo-Cu composites for thermal management applications because it allows the high thermal conductivity of Cu to be preserved without dilution through solid solution formation. The sharpening of XRD peaks after sintering indicates some degree of recovery and grain growth during the SPS process. However, the rapid heating rates and short dwell times characteristic of SPS help minimize excessive grain growth compared to conventional sintering methods.

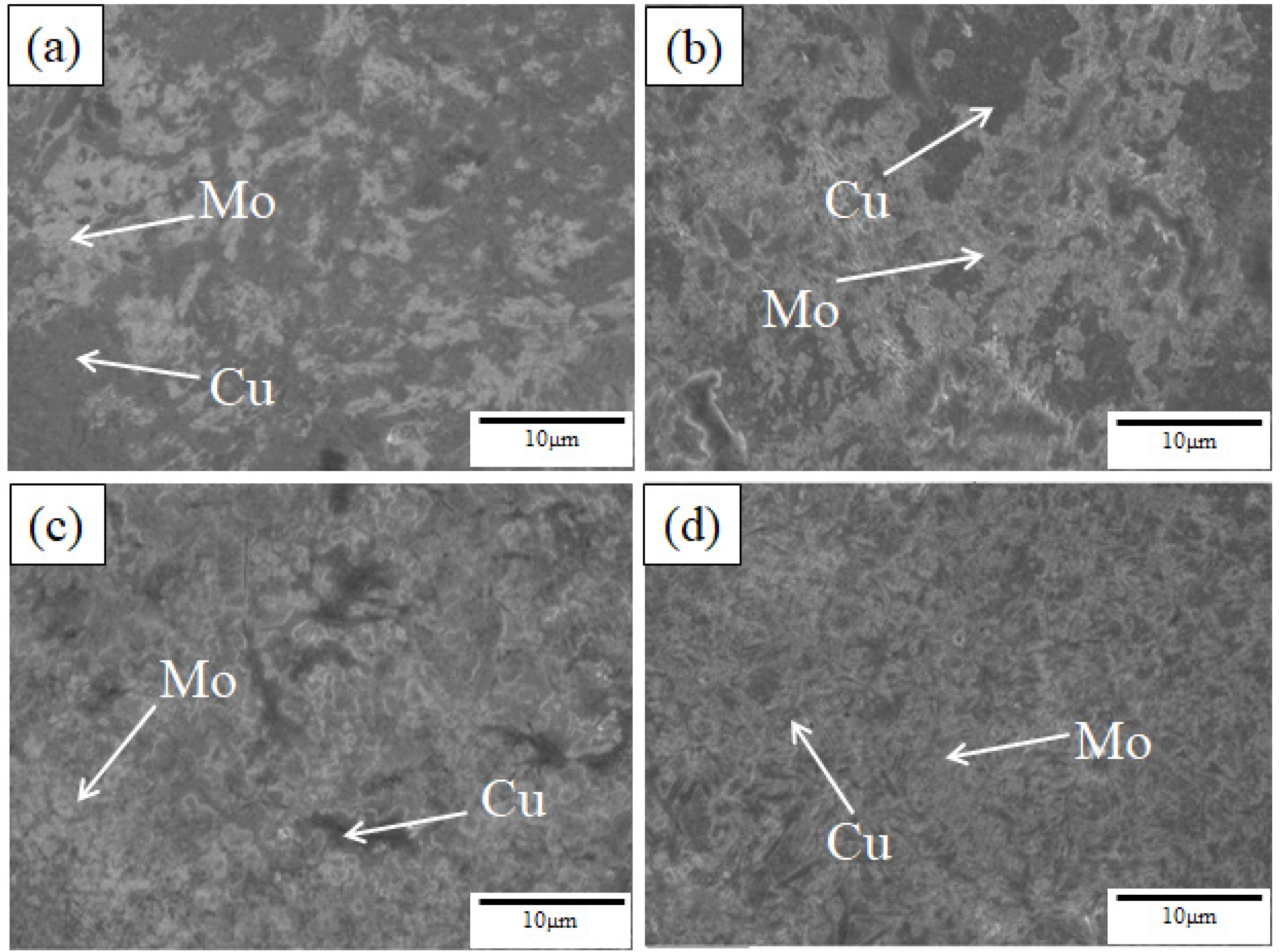

Fig. 3(a), (b), (c) and (d) show the SEM images of the Mo-Cu composites. SEM images of the sintered Mo-Cu composites show that the bright regions correspond to Mo, while the dark regions represent Cu. The microstructure exhibits a heterogeneous distribution of Mo particles within the Cu matrix. As the Cu content increases from 10 to 40 wt.%, the continuity of the Cu phase improves, and the porosity decreases, consistent with the measured relative density. In the Mo-10Cu composite, isolated Cu regions are observed within a predominantly Mo matrix with noticeable porosity. As the Cu content increases to 20 and 30 wt.%, a more interconnected Cu network begins to form, reducing the porosity. In the Mo-40Cu composite, a continuous Cu matrix with dispersed Mo particles is observed, exhibiting the lowest porosity among all compositions. The preservation of fine microstructure can be attributed to the rapid heating and short dwell time characteristic of the SPS process, which minimizes grain growth compared to conventional sintering methods. The interface between Mo and Cu phases plays a crucial role in determining both thermal and mechanical properties of the composites. Despite the immiscibility of these elements, the high-pressure conditions during SPS promote mechanical bonding at the interfaces. The quality of these interfaces affects interfacial thermal resistance, which influences overall thermal conductivity.

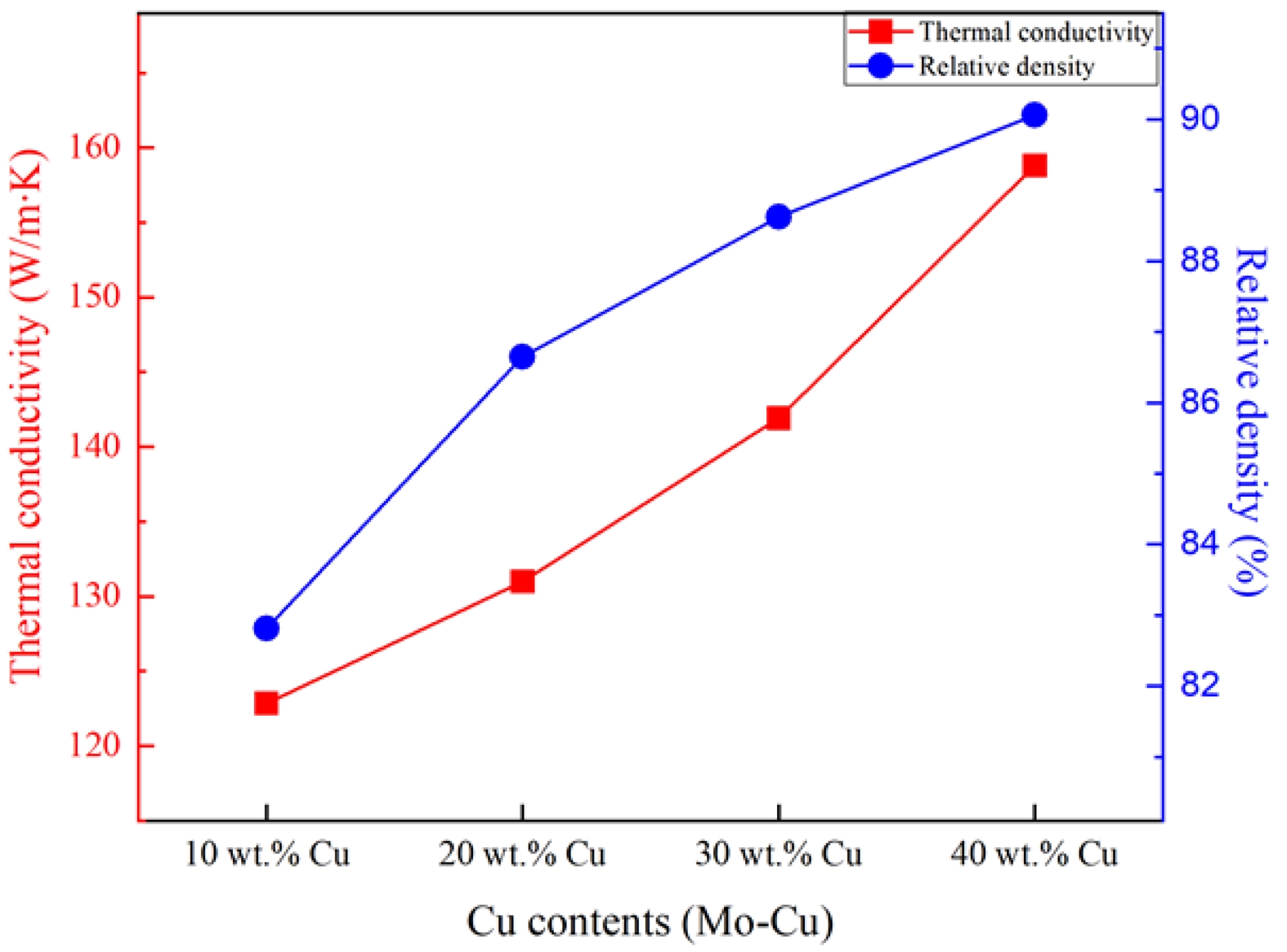

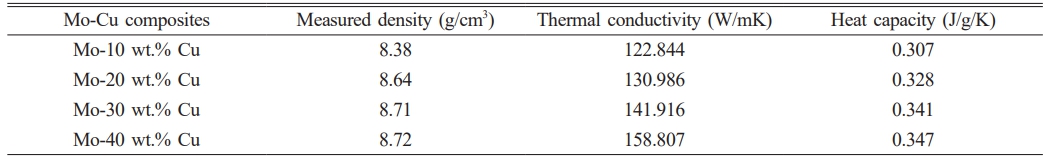

Fig. 4 shows the thermal conductivity and relative density of Mo-Cu as a function of Cu content. The thermal conductivity increases from 122.8 W/m·K for Mo-10Cu to 158.8 W/m·K for Mo-40Cu. This enhancement can be attributed to two primary factors: (1) the inherently higher thermal conductivity of Cu (398 W/m·K) compared to Mo (138 W/m·K), and (2) the reduction in porosity with increasing Cu content, as confirmed by the relative density measurements. In composite materials, thermal conductivity depends on both the intrinsic conductivity of the constituent phases and the interfacial thermal resistance. As the Cu content increases, the formation of continuous Cu pathways facilitates heat transfer through the composite, leading to higher thermal conductivity. Moreover, the decrease in porosity reduces phonon scattering at void interfaces, further enhancing thermal conduction. The improvement in thermal conductivity is correlated with both the intrinsic high thermal conductivity of the Cu phase and the resulting reduction in porosity; however, the enhancement is primarily and most strongly attributed to the intrinsic high thermal conductivity of Cu. Cu possesses a high intrinsic thermal conductivity (approximately 398 W/m·K) compared to that of Mo (138 W/m·K). As the Cu content increases from 10 wt.% to 40 wt.%, the higher volume fraction of the superior conductive phase introduces continuous, low-resistance pathways for heat transfer throughout the material. This is consistent with the microstructural transition observed from isolated Cu regions to a continuous Cu matrix, which significantly facilitates thermal flow. The experimental values are lower than those predicted by the rule of mixtures, which can be attributed to interfacial thermal resistance between Mo and Cu phases, as well as the presence of porosity [24]. The thermal conductivity values obtained in this study (122.8-158.8 W/m-K) are within the range reported for similar Mo-Cu composites in the literature [25], lower values were obtained than expected, and this difference can be attributed to the increase in interfacial thermal resistance due to residual porosity and the presence of a potential oxide film at the interface of the SPS processed composites.

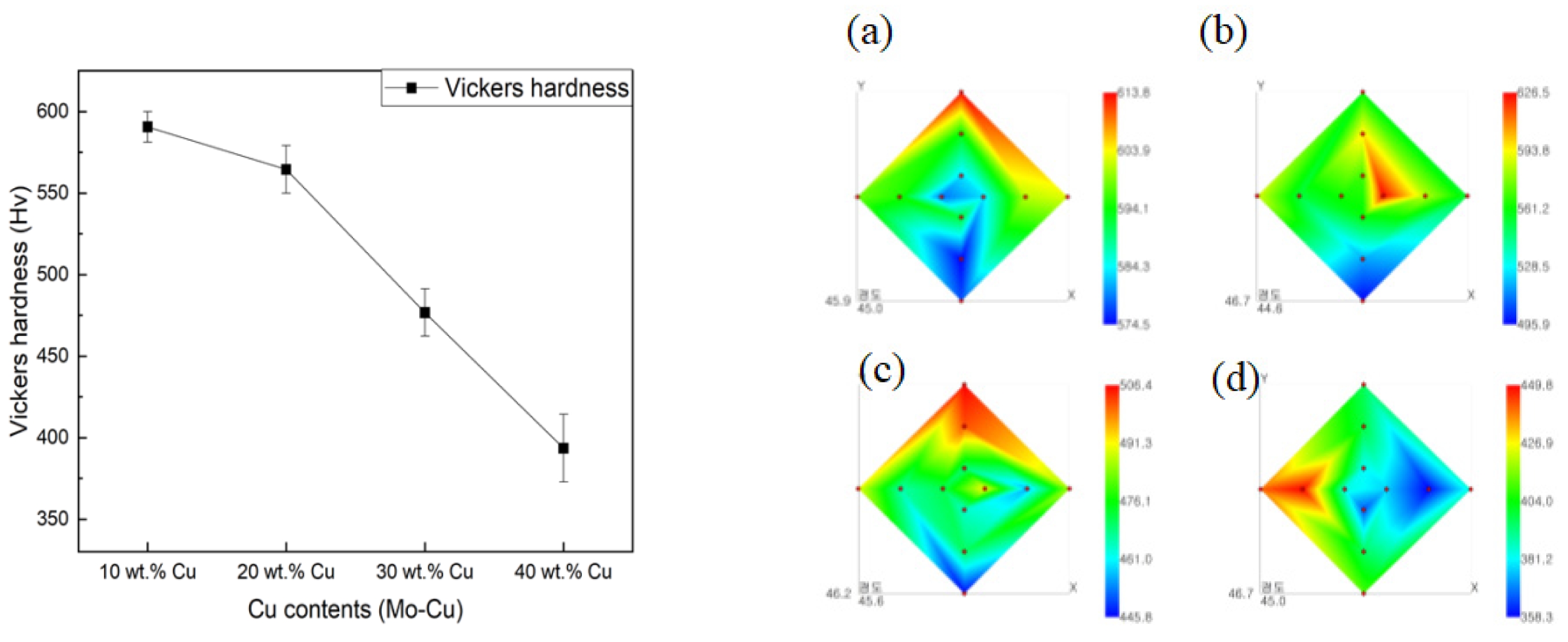

Fig. 5 shows the average hardness calculated from 100 indentations generated by a Vickers hardness and contour plots of 12 points Vickers hardness(a), (b), (c), and (d). For each Mo-Cu composite composition, a total of 100 individual Vickers indentations were measured. The final average hardness value reported in the graph for each composition represents the mean of the 98 measurements remaining after excluding the single maximum and single minimum values. The error bars shown in Fig. 5 indicate the standard deviation calculated from these 98 measurements for the respective composition. The Vickers hardness decreases from 591.2 Hv for Mo-10Cu to 395.2 Hv for Mo-40Cu. This trend can be explained by considering the intrinsic hardness of the constituent materials and the microstructural characteristics. Mo exhibits significantly higher hardness (approximately 1400-2000 Hv) than Cu (approximately 40-120 Hv) due to its stronger atomic bonding and higher melting point. As the Cu content increases, the composite's hardness decreases due to the larger proportion of the softer Cu phase. Additionally, the microstructural changes associated with increased Cu content, such as the transition from a Mo-dominant matrix to a Cu-dominant matrix, contribute to the reduction in hardness. The hardness values observed in this study are comparable to those reported by Mv et al. [26] for similar metal matrix composites fabricated using spark plasma sintering. The slightly lower hardness compared to theoretical predictions based on the rule of mixtures can be attributed to the presence of porosity, particularly in the Mo-rich compositions, which reduces the effective load-bearing capacity. The relationship between hardness and microstructure in Mo-Cu composites can be analyzed using various strengthening mechanisms and composite models. In particle-reinforced metal matrix composites, hardness is influenced by several factors, including the volume fraction and intrinsic hardness of constituent phases, particle size and distribution, interface strength, and matrix grain size. For the Mo-Cu system, where no chemical reaction or significant mutual solubility exists, solid solution strengthening is minimal, and the primary strengthening mechanisms are dispersion strengthening and grain boundary strengthening. The transition from a Mo-dominant matrix to a Cu-dominant matrix with increasing Cu content significantly affects the hardness behavior. According to composite theory [27], when the harder phase (Mo) forms a continuous network, the composite exhibits higher hardness, approaching that of the harder phase. Conversely, when the softer phase (Cu) becomes continuous, the hardness decreases substantially, approaching that of the softer phase. This transition explains the more pronounced decrease in hardness observed between 20 and 30 wt.% Cu, which corresponds to the microstructural change from isolated Cu regions to an interconnected Cu network. table 1

|

Fig. 1 Shrinkage displacement with sintering time and temperature profile of the Mo-Cu composites as a function of Cu contents. |

|

Fig. 2 XRD patterns of Mo-Cu composites as a function of Cu contents: (a) HEBMed powders and (b) sintered-bodies. |

|

Fig. 3 Microstructures of the Mo-Cu composites sintered at 950 ℃: (a) Mo-10 wt.% Cu, (b) Mo-20 wt.% Cu, (c) Mo-30 wt.% Cu, and (d) Mo-40 wt.% Cu. |

|

Fig. 4 Thermal conductivity and relatve density of Mo-Cu as a function of Cu content. |

|

Fig. 5 Variation of mechanical property of the Mo-Cu composites and contour plots of 12 points vickers hardness of (a) Mo-10 wt.% Cu, (b) Mo-20 wt.% Cu, (c) Mo-30 wt.% Cu, (d) Mo-40 wt.% Cu. |

In this study, Mo-Cu composites with Cu content (10-40 wt.%) were successfully fabricated using high energy ball milling followed by spark plasma sintering. The influence of Cu content on the microstructure, densification behavior, thermal conductivity, and hardness was systematically investigated. The following conclusions can be drawn:

1. The relative density of the sintered composites increased from 82.8 to 90.1% with increasing Cu content from 10 to 40 wt.%, indicating that Cu enhances densification during the SPS process.

2. XRD analysis confirmed that no secondary phases formed during sintering at 950 °C, preserving the binary Mo-Cu composite structure.

3. Microstructural analysis revealed a transition from isolated Cu regions in a predominantly Mo matrix at low Cu content to a continuous Cu matrix with dispersed Mo particles at high Cu content, with corresponding reduction in porosity.

4. The thermal conductivity increased from 122.8 for Mo-10Cu to 158.8 W/m-K for Mo-40Cu, which is attributed to the high intrinsic thermal conductivity of Cu and the decrease in porosity with increasing Cu content.

5. The Vickers hardness decreased from 591.2 for Mo-10Cu to 395.2 Hv for Mo-40Cu, consistent with the higher proportion of softer Cu phase and the transition in matrix dominance from Mo to Cu.

This study has been conducted with the support of the Korea Institute of Industrial Technology as “Development of a remote manufacturing system for high-risk, high-difficulty pipe production processes” (KITECH EH-25-0004).

- 1. A.L. Moore and L. Shi, Mater. Today 17 (2014) 163-174.

-

- 2. J.H. Jang, H.K. Park, J.H. Lee, J.W. Lim, and I.H. Oh, Composites, Part B 183 (2020) 107735.

-

- 3. A.R. Dhumal, A.P. Kulkarni, and N.H. Ambhore, J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 70 (2023) 140.

-

- 4. R. Mahajan, R. Nair, and V. Walkharkar, Intel Technol. J. 6 (2002) 55-61.

- 5. R. Kandasamy, X.Q. Wang, and A.S. Mujumdar, Appl. Therm. Eng. 27 (2007) 2822-2832.

-

- 6. C.W. Nan and R. Birringer, Phys. Rev. B 57 (1998) 8264-8268.

-

- 7. K. Chu, H. Guo, C. Jia, F. Yin, X. Zhang, X. Liang, and H. Chen, Nanoscale Res Lett 5[5] (2010) 868-874.

-

- 8. J.T. Yao, C.J. Li, Yi L, B. Chen, and H.B. Huo, Mater. Des. 88 (2015) 774-780.

-

- 9. D. Srinivasan and P.R. Subramanian, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 459 (2007) 145-150.

-

- 10. Z. Chen, W. Kang, B. Li, Q. Zhang, X. Hu, Y. Ding, and S. Liang, J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24 (2023) 715-723.

-

- 11. J.L. Johnson, Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 53 (2015) 80-86.

-

- 12. J. Ma, W. Chen, F. Yao, X. Zhou, and Y.Q. Fu, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 915 (2024) 147276.

-

- 13. V. deP. Martinez, C. Aguilar, J. Marin, S. Ordoñez, and F. Castro, Mater. Lett. 61 (2007) 929-933.

-

- 14. C.C. Koch, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 244 (1998) 39-48.

-

- 15. O. Guillon, J. Gonzalez-Julian, B. Dargatz, T. Kessel, G. Schierning, J. Räthel, and M. Herrmann, Adv. Eng. Mater. 16 (2014) 830-849.

-

- 16. J.H. Lee and H.K. Park, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 22 (2021) 655-664.

-

- 17. T. Nishimura, M. Mitomo, H. Hirotsuru, and M. Kawahara, J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 15 (1995) 1046-1047.

-

- 18. X.X. Li, C. Yang, T. Chen, L.C. Zhang, M.D. Hayat, and P. Cao, J. Alloy. Compd. 802 (2019) 600-608.

-

- 19. B.S. Park, J.H. Lee, J.C. Park, and H.K. Park, J. Alloys Compd. 984 (2024) 173900.

-

- 20. J.H. Kim, J.H. Lee, J.H. Jang, I.H. Oh, S.K. Hong, and H.K. Park, Korean J. Met. Mater. 58[8] (2020) 533-539.

-

- 21. F.A. da Costa, A.G.P. da Silva, and U.U. Gomes, Powder Technol. 134 (2003) 123-132.

-

- 22. Y. Yu, C. Wang, Y. Li, X. Liu, R. Kainuma, and K. Ishida, Mater. Chem. Phys. 125 (2011) 37-45.

-

- 23. X. Bai, T.L. Wang, N. Ding, J.H. Li, and B.X. Liu, J. Appl. Phys. 108 (2010) 073534.

-

- 24. B.K. Jang, J. Alloys Compd. 480 (2009) 806-809.

-

- 25. B. Li, H. Jin, F. Ding, L. Bai, and F. Yuan, Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 73 (2018) 13-21.

-

- 26. M.V. Reddy, P.K. Sahoo, A. Krishnaiah, P. Ghosal, and T.K. Nandy, J. Alloys Compd. 941 (2023) 168740.

-

- 27. K.U. Kainer, Metal Matrix Compos. (2006) 1-54.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 909-915

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.909

- Received on Aug 21, 2025

- Revised on Oct 10, 2025

- Accepted on Oct 28, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

introduction

experimental procedure

results and discussion

conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Hyun-kuk Park

-

Purpose-based Mobility Group, Korea Institute of Industrial technology, Gwangju 61012, Republic of Korea

Tel : +82-62-600-6270 Fax: +82-62-600-6149 - E-mail: hk-park@kitech.re.kr

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.